REVIEWING sale prices and averages can often lead to a range of conversations among commercial beef producers. Recent dialogue around the top sale process by some producers focused on the same commercial returns for steers, regardless of the actual value of the sires used.

As one producer stated during a recent discussion I was involved in:

“Even if you purchase a $200,000 bull, the processors will still pay you the same for your steers that perform and grade the same as those from a $1500 bull.”

While there may be some truth in this comment, it is also misleading. Trying to equate investment in genetic improvement with sale price per head is a very crude measure, which overlooks many of the factors that actually contribute to productivity in a beef breeding program.

Profitability is driven by two key factors. Sale price, ($/kg dressed, or live) often is the most reviewed and discussed by producers. There is often an overwhelming fixation among producers on the price paid and the variations of price offered on breed type or other criteria.

While price per kilogram is an integral factor in enterprise profitability, the average price per kilogram producers received for their livestock accounts for around 20pc of the variation in profitability across beef enterprises.

The major contributor to profitability within beef enterprises is the cost of production. Numerous industry benchmarking projects have demonstrated the variation in cost of production far outweighs the impact of average price per kilogram.

And while there is often a temptation among producers to focus only on reducing costs within the management program, these studies have shown that the biggest influence on a business’s cost of production is the amount of red meat produced and sold per hectare.

Two distinct payoffs

For any beef business wanting to increase its profit margin, increasing kilograms of beef produced is a more likely to have a meaningful impact than attempting to slash costs or to try to chase a few extra cents at sale time.

This isn’t to say that producers should disregard their cost structure or overlook opportunities that may exist through more targeted marketing. However, in many cases producers invest more time in these areas than may be justified for the slight increase in profit margin that they may achieve. This is particularly true when comparing these increases against improvements achieved through more efficient production.

Investment in genetics can offer producers advantages in their efforts to make improvements. While the initial investment can be seen as an increased cost, there are flow-on benefits that offer returns over a long period.

The payoff that genetic improvement offers is seen in two distinct ways in a beef business.

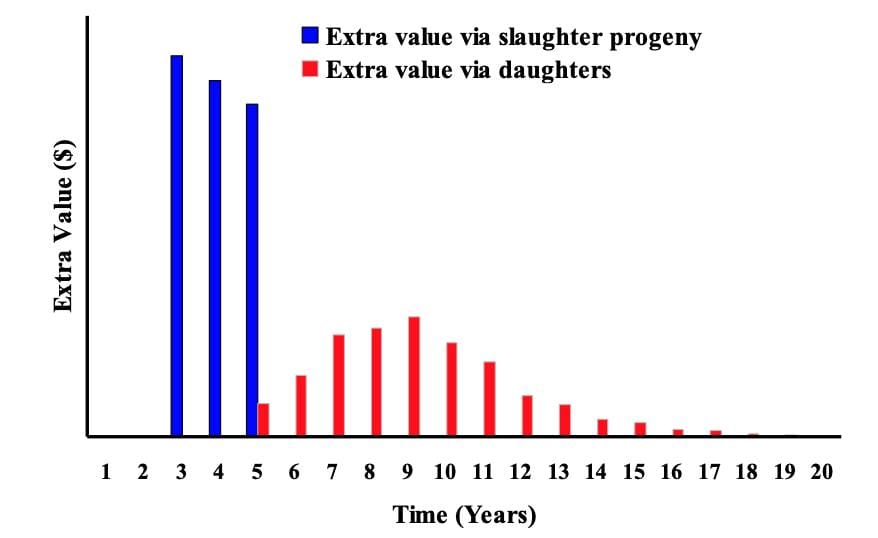

The first is through the improvements associated with the sale of progeny that display greater performance – either through faster growth and earlier turn off, or by increased weights at the same turn off time (Figure 1)

Fig 1: The flow on benefits from genetic improvement

The second, and often a greater improvement in herd productivity and profitability is seen with the replacement females which then enter the herd.

It can often be easy to overlook the impact that increased weight at joining, achieved through better genetics for growth, will have on a herd fertility levels.

Combine this improvement with improvements in other traits such as calving ease, shorter gestation lengths and shorter days to calving and the cumulative impact on the production levels within a herd becomes significant.

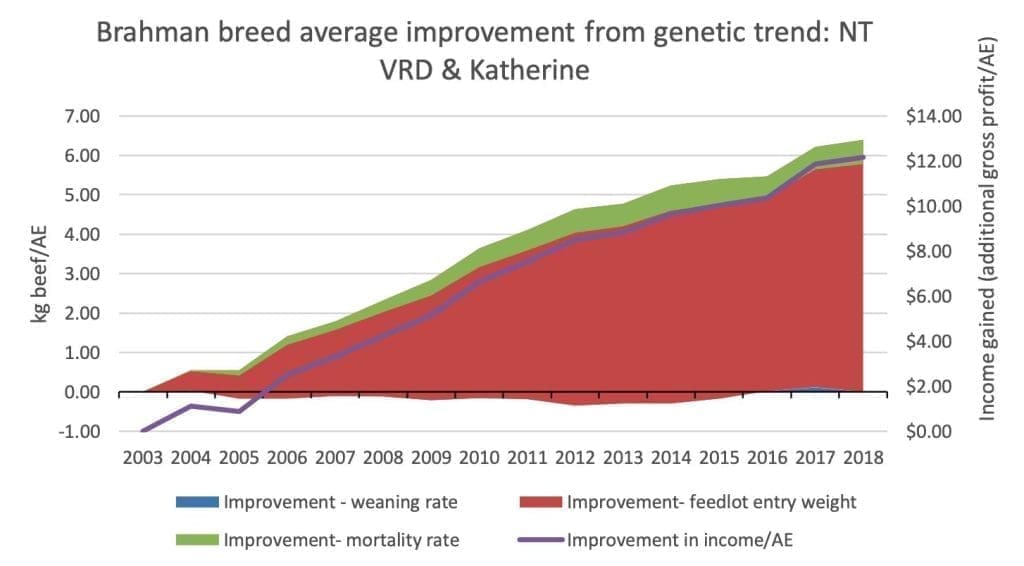

The MLA report “Proof of Profit from EBV based selection” prepared by AGBU and BushAgribusiness in 2020 demonstrated the cumulative impact that selection for greater genetic merit can have on commercial herds.

The report found that genetic gain for the Brahman breed average between 2003 and 2018 generated an additional $12/Adult Equivalent (AE) in the NT, while for Hereford producers following breed average trends in the same period the increase was $25/AE.

Cumulative productivity and income/AE gain itemised for each productivity driver over the period. Source: MLA “Proof of Profit from EBV Based selection”

The cumulative benefit that is available to all beef producers through genetic investment shouldn’t be overlooked. While breed averages do allow for improvements, selection for sires that are above breed average have been found to lift the cumulative profit to higher levels.

The MLA study found the difference in the profitability of the southern programs top 25pc was 1.5 times greater than the bottom 25pc, on an Adult Equivalent basis.

So while it is often tempting to focus only on the price received for steers sold this year, the reality is this isn’t a fair indication of a herd’s profitability – let alone the purchase price of a new bull.

To genuinely understand a business’s profits, producers need to look deeper into their production system.

In doing this, they will not only have a greater chance to address the key drivers of profit for their circumstances, but they will also have a better opportunity to select sires that can help drive long term cumulative herd improvements and profits.

Alastair Rayner is the Principal of RaynerAg, an agricultural advisory service based in NSW. RaynerAg is affiliated with BJA Stock & Station Agents. He regularly lists and sell cattle for clients as well attending bull sales to support client purchases. Alastair provides pre-sale selections and classifications for seedstock producers in NSW, Qld, and Victoria. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au

Alastair Rayner is the Principal of RaynerAg, an agricultural advisory service based in NSW. RaynerAg is affiliated with BJA Stock & Station Agents. He regularly lists and sell cattle for clients as well attending bull sales to support client purchases. Alastair provides pre-sale selections and classifications for seedstock producers in NSW, Qld, and Victoria. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au