GENETIC selection offers producers long-term and cumulative changes within their herd – however the challenge is to have a clear objective to focus on when making selection decisions.

Without a clear objective, or a defined starting point, the opportunities for genetic improvement go unrecognised, or are underwhelming for cattle business operators.

The lack of clear starting points to make improvements, or a lack of focus, can often lead to the introduction of less desirable traits. And as genetics is cumulative, these traits can become more pronounced and result in more problems for a herd, rather than an improvement.

Geoff Fordyce

Recently I attended the Northern Beef Producers Field Days in Charters Towers and was able to catch up with recently retired Dr Geoffrey Fordyce, a long-time and highly-respected northern beef researcher.

Over a number of subjects we discussed, one particular topic has given me much to consider. That is the topic of the language we use (or perhaps tp put it another way, the metrics we measure), and how this impacts on our ability to measure herd performance and make subsequently make improvements for the longer term.

Geoffrey highlighted the risk with language and in particular the units of measurement used more generally in beef industry.

Many of these units – for example the percentage weaned, or branding percentage – are highly variable. Much of this variability is due to the variation in starting values.

Producers who lack accurate records on total cow numbers introduce inaccuracies to the calculations that then produce inaccurate fertility percentages.

The comment Geoff made to me at the time was that, “We don’t actually get paid on percentages – we get paid on kilograms produced and sold.”

With this as a fundamental starting point, focusing on what producers are paid for, this may actually be a more accurate starting point to use when determining a process for selection of genetics to move a herd forward.

In practice, this means producers should be considering how many kilograms of beef has been produced from the business’s available grazing area on an annual basis. In understanding how much has been produced, it quickly becomes evident where focus needs to be placed in order to increase beef enterprise profitability.

As a concept for genetic selection, this is fundamental. It is easy to get excited by the opportunity to select animals with higher genetic merit for traits such as growth, calving ease or eating quality.

However if the amount of beef annually produced is low, or variable, the opportunity to capitalise on these traits is very limited.

Importance of livestock schedules

Perhaps the basic commencement of the process of evaluating annual production is to ensure a breeding herd has an actual livestock schedule.

It is concerning that many businesses struggle to complete an accurate schedule for the year. However, for those producers who take the time, they can unlock a significant amount of information directly related to their business. In simplest terms, a livestock schedule records all transactions for a year and is reconciled by an actual stock-take at the opening and closing of the year.

To make the process more efficient, the schedule should really categorise cattle on hand by sex and age groups – with the most effective grouping based on the two or three youngest age groups and one mature group.

Any transactions during the year are recorded against these groups. Producers who make time to accurately record this data are able to quickly evaluate the amount of actual liveweight in each category and determine what amount has been sold.

The data also allows producers to quickly home-in on production, particularly production per hectare by dividing liveweight production by the total grazing area.

One of the fundamental strengths of this approach is the removal of variability in measurement from calculations. The data is fixed on kilograms produced and sold.

This along with grazing area are two fixed points of reference. This allows the opportunity to make real comparisons on production, rather than estimations based on changing variables such as weaning or branding percentage.

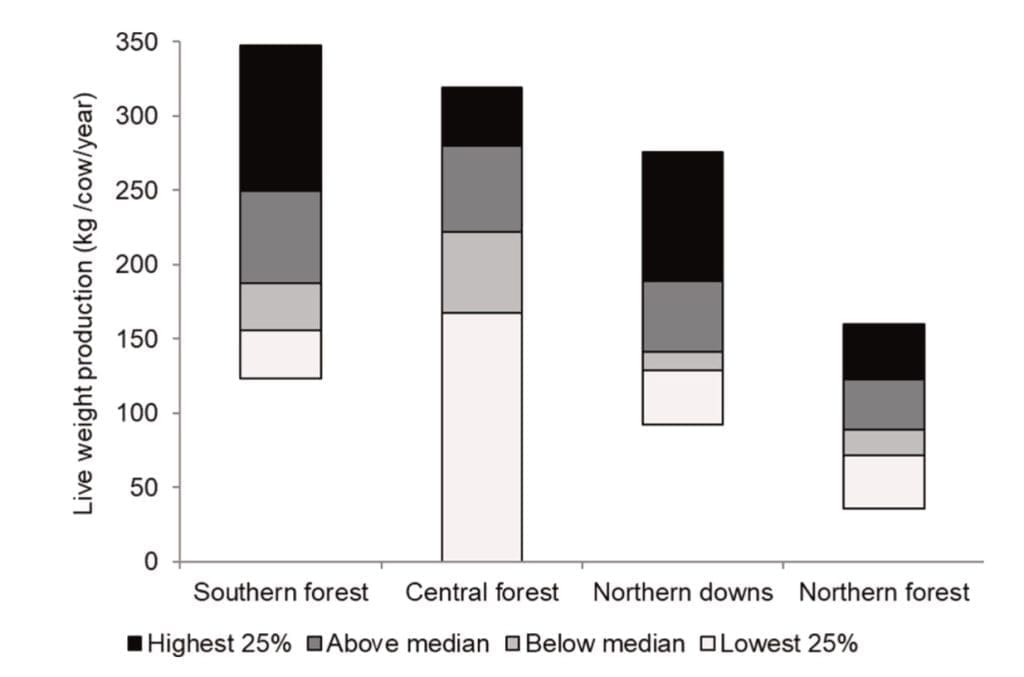

The well-known, ground-breaking Cash Cow project run in Queensland, demonstrated the significant range of annual liveweight production across northern herds. The project identified across a range of environments, that the variation in production was as much as double when looking between the highest and lowest for herds in the project.

Cash Cow results demonstrating variation in live weight production across north Australian beef herds in four primary country types (McGowan et al., 2014).

The opportunity presented for producers, across all regions of Australia, is to reconsider the data they are using to make their selection and ultimately their business decisions.

Geoffry Fordyce highlights that there is considerable genetic variation within herds, but there is actually less variation between herds. In the case of using selection to improve liveweight production, there is considerable scope to lift productivity through animal that wean a calf every 12 months.

“These are females that have a much higher inherent ability to produce liveweight from available pasture than low fertility cows. You can see this in those cows higher liveweight production, heavier weaners, and better body condition at weaning,” he said.

Refocusing attention to measurements that are fixed offers greater scope to capitalise on opportunities across a beef business.

While some producers may need to refresh their methods of data collection, the longer-term opportunities resulting from this action are likely to lead to greater and more effective business improvements.

Alastair Rayner is the Principal of RaynerAg, an agricultural advisory service based in NSW. RaynerAg is affiliated with BJA Stock & Station Agents. He regularly lists and sell cattle for clients as well attending bull sales to support client purchases. Alastair provides pre-sale selections and classifications for seedstock producers in NSW, Qld and Victoria. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au

Alastair Rayner is the Principal of RaynerAg, an agricultural advisory service based in NSW. RaynerAg is affiliated with BJA Stock & Station Agents. He regularly lists and sell cattle for clients as well attending bull sales to support client purchases. Alastair provides pre-sale selections and classifications for seedstock producers in NSW, Qld and Victoria. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au