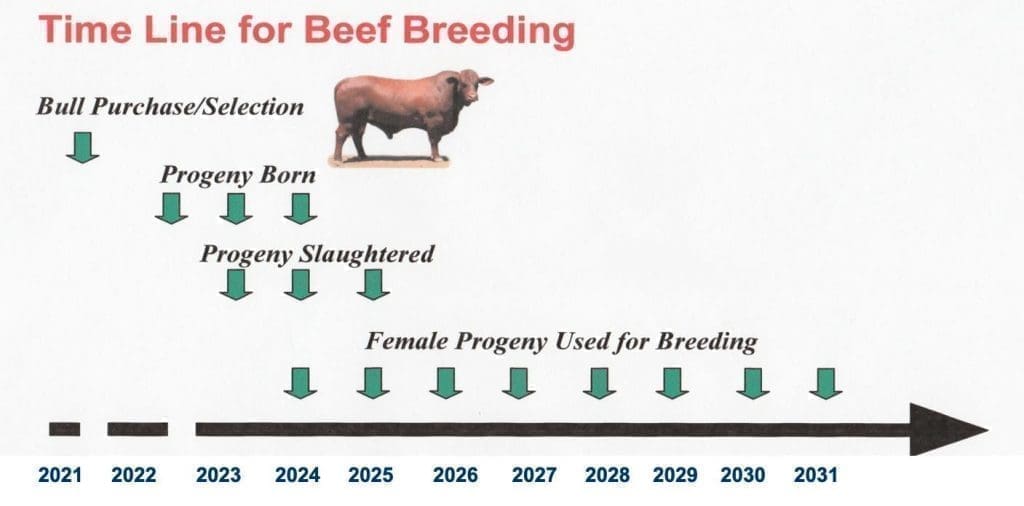

MAKING genetic change is a long-term undertaking in the beef industry. It is easy to appreciate the time associated with choosing a bull and seeing the resulting calves, but the longer-term changes are often more challenging to consider.

The timeline of impact a sire has on a herd has been highlighted previously in Beef Central genetics columns. A sire may directly influence 50 percent of the genes for steers born in his working life, and around eight age-groups of females, there is more to a herd’s make-up than this sire’s contribution.

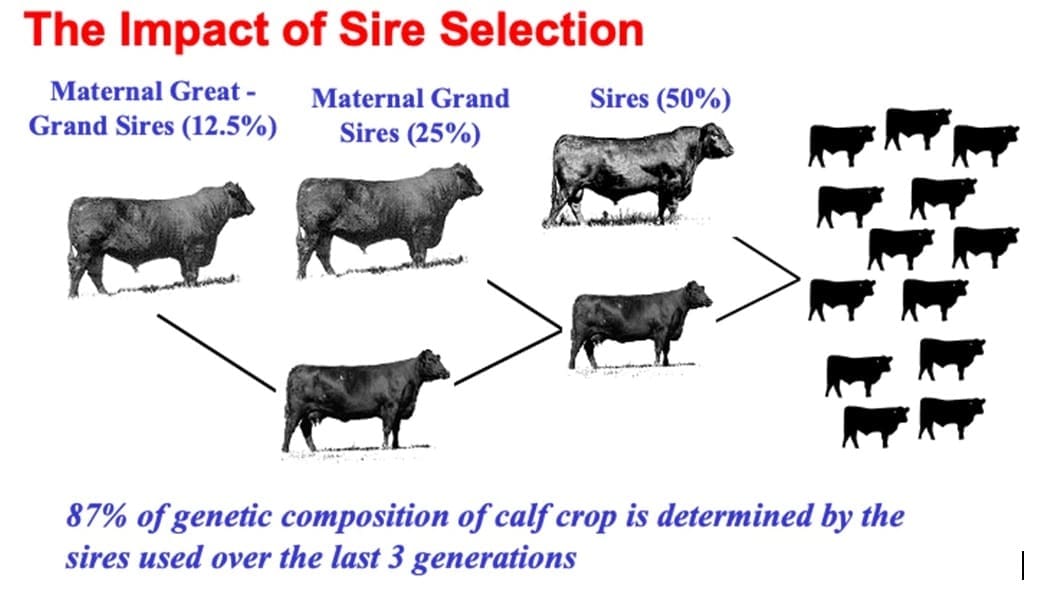

It’s important not to overlook the point that a cow also contributes 50pc of a steer’s genetics, and 50pc pf her daughters that are retained in the herd.

The challenge for many producers is to consider what are the genetic influences at play in the cow herd? The following diagram outlines the genetic composition of typical self-replacing breeder herds. In a practical context, the calves born in 2022 will be able to attribute 87pc of their genetic composition to the last three generations of sires used in the herd.

Getting the impact from ‘game-changers’

One of the challenges for many producers is to understand why a new sire has not had the impact on a herd that may have been expected.

Often a new bull entering a program is seen as a game-changer. However, the calves that are born often don’t seem to live up to expectations.

Much of that outcome can be attributed to the influence of the previous sires. Their genetic influence, expressed in the cow herd, can be the reason why calves are a bit disappointing or the progress in changing is slower than expected.

Increasing rate of change

There are ways to work to increase the rate of change. One area to consider is the generational interval, or average cow age, of the herd.

Herds with predominately older cows allow the influence of previous sires to be expressed over a number of years. This can impact on the degree in which a producer’s efforts to correct or increase traits can be realised. It can be a long process to correct a trait when the traits of concern are deeply embedded across the herd.

Increasing replacement rate, lowering the cow age, will help reduce the timespan those cows can have to influence a herd. However, this can have its own challenges in terms of maintaining sufficient replacement females.

More importantly, increasing replacement rates can result in less selection pressure being placed on replacement females. Ideally genetic change occurs more swiftly in herds with lower generational intervals and high levels of selection pressure on replacements.

As this isn’t always an option for commercial herds, there are practical alternatives.

Selection pressure can be placed on replacements, and particularly on new sires. Sires that are genetically superior should be used in preference to average sires. These sires can be found using Breedplan data.

More rapid progress can come through joining these to the better groups of replacement females first and finding ways to reduce generational intervals by placing more selection on older cows. Some useful strategies have been to focus on fertility though restricted joining and to set production measures such as calves weaned and on weaning weights that are above herd average.

These practical measures can be combined to bring some pressure across the herd and open the way to make more genetic progress toward a herd that is productive and profitable.

Alastair Rayner is the Principal of RaynerAg, an agricultural advisory service based in NSW. RaynerAg is affiliated with BJA Stock & Station Agents. He regularly lists and sell cattle for clients as well attending bull sales to support client purchases. Alastair provides pre-sale selections and classifications for seedstock producers in NSW, Qld and Victoria. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au

Alastair Rayner is the Principal of RaynerAg, an agricultural advisory service based in NSW. RaynerAg is affiliated with BJA Stock & Station Agents. He regularly lists and sell cattle for clients as well attending bull sales to support client purchases. Alastair provides pre-sale selections and classifications for seedstock producers in NSW, Qld and Victoria. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au