Cattle at one of the paddock supplementation sites at UQ Gatton used to assess the delivery of the methane reducing Bovaer feed additive to cattle in a paddock environment

A SYSTEM described as a world-first for the delivery of Bovaer methane-reducing feed additives to cattle in extensive environments was showcased during Beef 2024 in Rockhampton last week.

It’s long been recognised that while feedlots provide an ideal opportunity to distribute methane-inhibiting additives via mixed rations and controlled feeding, it’s a vastly different story in the extensive grass paddock environment. And Australian cattle typically only spend ten percent of their life cycle in feedlots, with the balance spent in grass paddocks.

One recent study suggested that at best, feeding anti-methanogenic feed additives at the feedlot stage typically only offsets between nine and thirteen percent of an animal’s lifetime methane output.

So unless efficient and reliable additive distribution systems can be developed for paddock environments, overall progress in livestock methane inhibition via additives is likely to be limited.

Dr Sarah Meale addresses the QAFFI seminar at Beef 2024 last week

University of Queensland researcher Dr Sarah Meale, from the School of Food Sustainability, spoke at two separate Beef 2024 seminars on the topic.

“If we try to tackle the grazing sector (as distinct from feedlots) in methane reduction using anti-methanogenic compounds, we actually have a huge opportunity to try and reduce some of those emissions,” Dr Meale told audiences.

“And alongside that we are seeing productivity gains in supplemented cattle as well. Not only do the compounds reduce methane, but increase productivity, effectively condensing the lifecycle of that animal – so you are doubling the effect,” she said.

A grazing trial was carried out last year at UQ Gatton using 150 composite heifers supplied by the North Australian Pastoral Co. One third were fed a simple lucerne pellet supplement, another third a higher energy grain-based pellet supplement, and the remainder a pellet containing both grain and Bovaer.

Full trial description and results below.

The trial – the world’s first field trial using Bovaer delivered in an attractant pellet form to paddock cattle – produced some interesting results.

One of the key findings was that the cost of using the additive was more than paid-for in the value of methane reductions (ACCU’s worth $12.58 per head) and productivity (weightgain) improvements meaning cattle reached feedlot entry weights 56 days earlier than the control group.

Dr Meale said one of the early findings was that what was provided in the pellet to attract cattle to the supplement site mattered.

“Pellets are very variable,” she said. “We did a behavioural study to figure out what worked best, starting with a lucerne-based pellet which produced variable results on a target of 1kg/day. Cattle came in regularly – consistently around 6-7am, but the mode of action in some methane-reducing additives requires more frequent access than that. In this system we were really trying to target getting the trial cattle back to visits to the site every 2-3 hours, which did not really occur with a lucerne-based pellet.”

However results improved significantly once grain-based pellets replaced lucerne pellets, producing much more consistent re-visits, and intake – even though the young cattle were running on “really good quality pasture.”

However results improved significantly once grain-based pellets replaced lucerne pellets, producing much more consistent re-visits, and intake – even though the young cattle were running on “really good quality pasture.”

Patterns started to emerge with re-visits to the feed distribution suite every couple of hours. Almost all of the consumption was between 6am and 6pm, with few visits later in the evening, Dr Meale said.

The project also looked at whether pellets carrying the anti-methanogenic compound maintained their integrity when stored in the feeding station’s hopper.

“It’s proven to be a really strong pellet, it stores well (without degradation or deterioration) and can be used in these extensive feed systems,” she said.

Earlier work

In some of her earlier research work carried out a decade ago while in France, Dr Meale looked into how early anti-methanogens should be introduced to an animal’s diet for optimum effect.

She found that in the first two weeks of life, all the methane-producing micro-flora establish in the calf’s rumen.

“If we can get something into their system soon after birth, potentially, we may be able to alter the rumen to reduce methane emissions for up to one year after we stop treating them,” she said, pointing to her paper published on the topic.

“If we can understand and implement this in an early-life setting, it has longer effects than just the treatment period,” Dr Meale said.

Methane reductions worth $12.58/head

In a separate presentation during the UQ/QAAFI seminar last week, Dr Meale provided first details about performance results from the grazing trial carried out at UQ Gatton.

She showed video footage of the mob of 150 young North Australian Pastoral Co composite cattle arriving voluntarily at an individual animal feeding station, with their RFID tag registered at entry, confirming which animals received a pellet-based ration containing Bovaer methane-inhibiting additive.

The trial was replicated over two different grazing seasons – summer and autumn last year.

Using Greenfeed in-field individual animal methane monitoring units, the cattle receiving the Bovaer supplement reduced their methane output by 25pc compared with cattle receiving the energy pellet only. Against the grazing-only (Lucerne pellet) group, the reduction was 31pc (per kilogram of average daily gain, taking into account differences in gain).

“Extrapolate that across a typical backgrounding period, a saving of 351kg of CO2 equivalent would be made, per beast, compared with the grazing only group, Dr Meale said.

“That’s $12.58 a head worth of carbon credits the producer would have access to. That essentially covers the cost of the supplement used – and then some,” she said.

Further details on the results will appear in the project paper when it is released, she said.

Productivity results

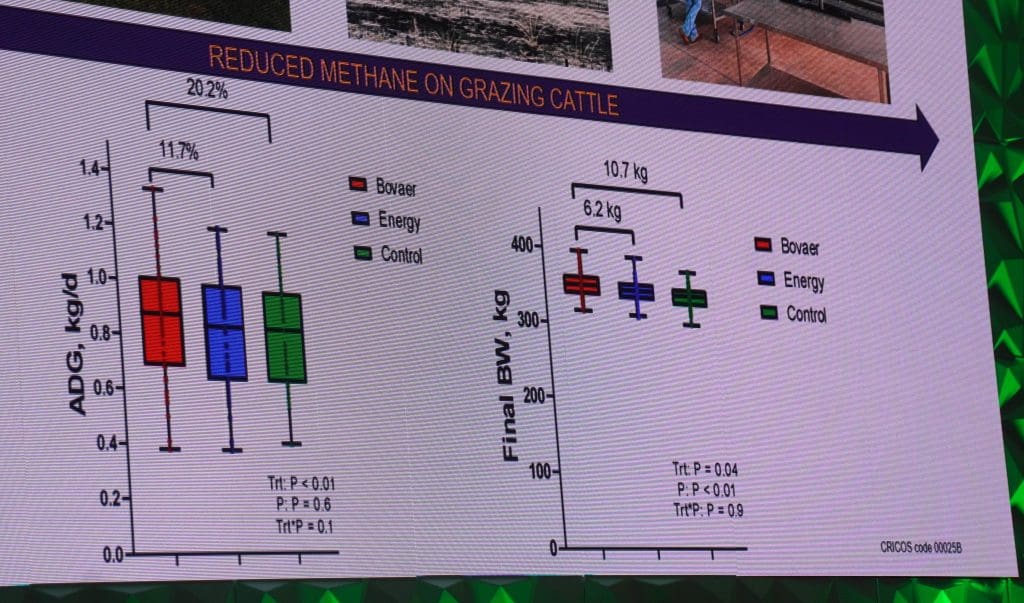

Asisde from the methabe inhibition results outlined above, University of Queensland PhD student Mariano Parra provided details of the animal productivity side of the Bovaer pellet paddock trial.

The heifer group supplemented with energy pellets containing Bovaer gained 20.4pc more weight than the unsupplemented paddock group, and 11.7pc more than those fed energy pellets alone.

The energy pellet+Bovaer group was 10.7kg heavier on average than those fed lucerne pellets, and 6.2kg heavier than the group supplemented with energy pellets.

“The trial demonstrates increased cattle performance, in addition to methane reduction,” he said.

“Our prediction suggests that supplementing Bovaer allows cattle to reach their liveweight required for feedlot entry 56 days earlier than those supplemented with lucerne pellets, and 26 days earlier than backgrounders fed energy pellets.”

Mr Parra said one of the next steps for the trial was to determine any differences in pasture consumption.

- Stand by for separate stories on the Greenfeed individual animal methane sampling technology, and an interview with the inventor of Bovaer Maik Kindermann, who spent time at Beef 2024 last week.