Precision Pasutres’ Hamish Webb explains some of the ins and outs of soil carbon farming. Photo: Mike Terry

WHEN Hamish and Jess Webb purchased Myanbah on the Northern Tablelands of New South Wales, the property was in the middle of the 2019 drought, suffering a series of nutrient deficiencies and stocking rates were low.

It led them to start a soil carbon project and subsequently become involved in the new industry. Mr Webb gave this week’s Nature Based Solutions conference a rundown of why they started the project and what they are hoping to achieve.

He said his knowledge of the carbon industry was limited before he started and coming from semi-arid climates in Western Qld and South Australia, they had plenty to learn about grazing the Northern Tablelands.

“There was one reason we wanted to look at a soil carbon project and that is because we wanted to improve our pasture,” he told the conference.

“We had a major pH or acidity problem, we had major deficiencies of phosphorus, potassium and sulphur and we were told we had low carbon levels.”

The Webbs employed the help of Milton Curkpatrick from Precision Pastures, a company for which Mr Webb is now the interim CEO and executive director.

“Milton said ‘this is not unusual’, the pH problems can be fixed by applying lime, the deficiencies can be fixed by applying fertiliser or compost and we can look at a pasture improvement program,” he said.

“I was scratching my head thinking, ‘how much is this going to cost?’ Then Milton said these were all changes that would be eligible for a soil carbon sequestration project.”

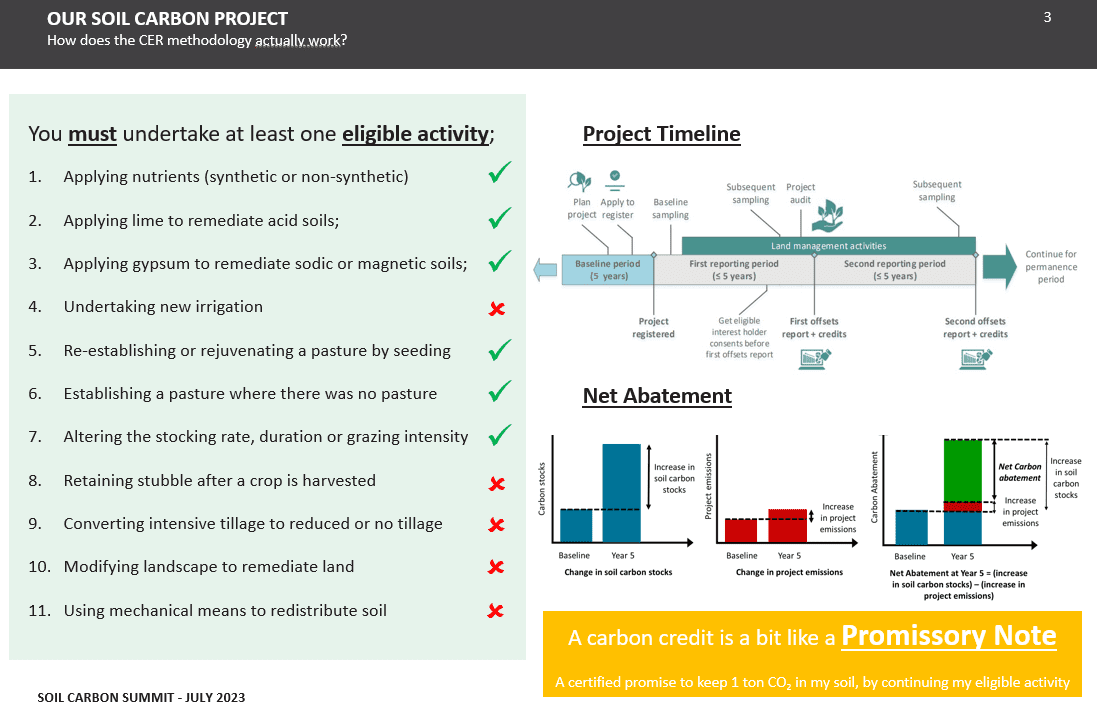

Tasked with working out how to start a soil carbon project, Mr Webb started researching news articles, websites and the eligible activities on the Clean Energy Regulator website.

“Just to follow Milton’s recommendations, we were planning to undertake six of the eligible activities,” he said.

Trials begin on Myanbah

With the project in mind, the Webbs started a trial on Myanbah – where they applied lime and sowed a perennial pasture mix of three types of clover and a tillage radish on two paddocks.

“Three years after undertaking our pasture improvement program we had achieved a 72 percent increase in production,” he said.

“You would expect that after improving pastures, but we did not expect the increase in carbon. In three years, we had achieved a 0.24pc increase in carbon.”

The Webbs then formed their own target to increase soil carbon across the entire 1200ha property by 1pc over the next 25 years.

Do the numbers add up?

Cost is one of the main aspects that often dominates discussion about soil carbon projects and Mr Webb broke down all the costs with rough estimates – starter report, project registration, mapping, two rounds core sample collection, two rounds of lab testing, annual monitoring and audit.

“It became pretty clear to us that for a potential investment of about $260,000, not including commission to our service provider, we could potentially generate $3m to $5m,” he said.

“If you look at it another way, for us to break even and cover the cost, we will need to increase our soil carbon by 0.05pc – we did five times that in our trial. So, we started to get comfortable with the risk in our capital outlay.”

Soil carbon not “a free gift”

Mr Webb finished by mentioning that soil carbon is not a free gift to producers and it required work to build carbon.

“Soil carbon can be a win-win, but it is not a free gift, you need to work at it,” he said.

“We have done some work to establish a target of what we can achieve and have done some work to align a soil carbon project with our production objectives. All of the clients at Precision Pastures goes through the same process, it is not about getting registered and the credits will roll in.”