AA Co sustainability and environment head Naomi Wilson address TropAg this week

THE price of methane-inhibiting feed additives would have to come down significantly to make financial sense for the world’s largest beef producer, the Australian Agricultural Co.

Naomi Wilson, head of environment and sustainability with AA Co, gave an account of her company’s progress towards a ‘nature positive’ approach to beef production during the enormous TropAg tropical agriculture conference being held in Brisbane this week.

More than a thousand delegates from across the world are attending the conference – mostly from the research community.

AA Co launched its sustainability framework in November last year, built around the purpose of evolving together to benefit future generations. The framework is built around three central pillars:

- Re-imagining agriculture – re-shaping agriculture to meet the needs of a rapidly changing world – meeting the needs of customers and society at large

- Valuing nature – respecting the foundation of the natural asset from which beef is produced, and

- Thriving communities, with people at the core of everything the company does as a business

“As we work towards this concept of nature-positive beef, how that is defined and what it means is the challenge in front of us,” Ms Wilson told the gathering.

“And how we deliver on it is even more of a challenge.”

In the field of climate action and natural capital, Ms Wilson said AA Co made the commitment to ‘take climate action’ because the company recognised that there were some significant challenges ahead and it needed to be active in addressing them.

Emissions

Drawing from AA Co’s annual sustainability report, Ms Wilson said the company’s financial annual emissions profile suggested it produced about 514,000t of carbon equivalent, emitted from about 380,000 head of cattle in the company’s operations across 28 properties on 6.5 million hectares of land.

“About 84pc of that output was enteric methane emissions – a very significant portion – and as mentioned by an earlier speaker, Australian methane emissions sat very strongly within the northern beef herd,” she said.

“About 84pc of that output was enteric methane emissions – a very significant portion – and as mentioned by an earlier speaker, Australian methane emissions sat very strongly within the northern beef herd,” she said.

To put AA Co’s methane emissions into perspective, it represented the equivalent of driving around 100,000 cars a year.

In taking climate action, AA Co had made a strong commitment to tackling the methane issue, Ms Wilson said.

“We can’t work through this discussion as an industry, and as a community, without doing something about methane. But we as a company are also going to look at how we can leverage our landscapes to drive carbon sequestration, and what those opportunities might be; and are doing work in GHG efficiency, primarily through genetic selection for methane efficiency in livestock.”

No carbon-neutral target

Ms Wilson said when AA Co released its sustainability strategy, it made a conscious decision not to set a carbon neutral target.

“It was evident through talks presented earlier at this TropAg conference that we don’t know how to get there yet,” she said.

“If we set a target, we don’t yet know how to achieve it. Instead, we have focussed on taking practical action, developing and contributing to the industry development of some of the solutions for the challenge in front of us.”

Among AA Co’s early work, it has partnered with asparagopsis (methane inhibiting) seaweed producer SeaForest and university reseachers to begin to fast-track the application of asparagopsis in cattle systems. The product’s performance in the lab was quite different from how that applied in the real world, Ms Wilson said.

“Certainly there are questions about how it functions in the paddock, and particularly in northern Australian diets,” she said.

“We need to understand how we tackle the science from the asparagopsis trials in a lab on 80-100 day fed animals and apply that in the real world.”

But SeaForest was already innovating in quite amazing ways, Ms Wilson said.

“One example is taking the product from a freeze-dried state which is delicate to work with – particularly in a northern environment – and infusing it into an oil which is stable to around 80 degrees C. So we are starting to see some innovation that might help us solve how we deliver the product to our animals.”

Currently AA Co has 80 head on a 300-day trial with UNE Tullimba feedlot, which will provide a better understanding about how asparagopsis performs in a Wagyu longfed program.

“We have a range of questions we are attempting to answer through that work. Obviously methane abatement is the number one, but there’s a whole lot of other questions that arise, as a producer. What’s the associated animal performance impact? What are the animal health and welfare implications, when potentially feeding this product to an animal across its entire lifespan of up to ten years? What about integrity and food safety?”

“There’s a whole range of questions when you start to take a product out of the lab into a commercial application.”

First results from the trial are due early 2023.

“It’s the first step, but there’s much, much more work to do in bringing this product into something we can use commercially,” Ms Wilson said.

Operational applications, big cost limitations

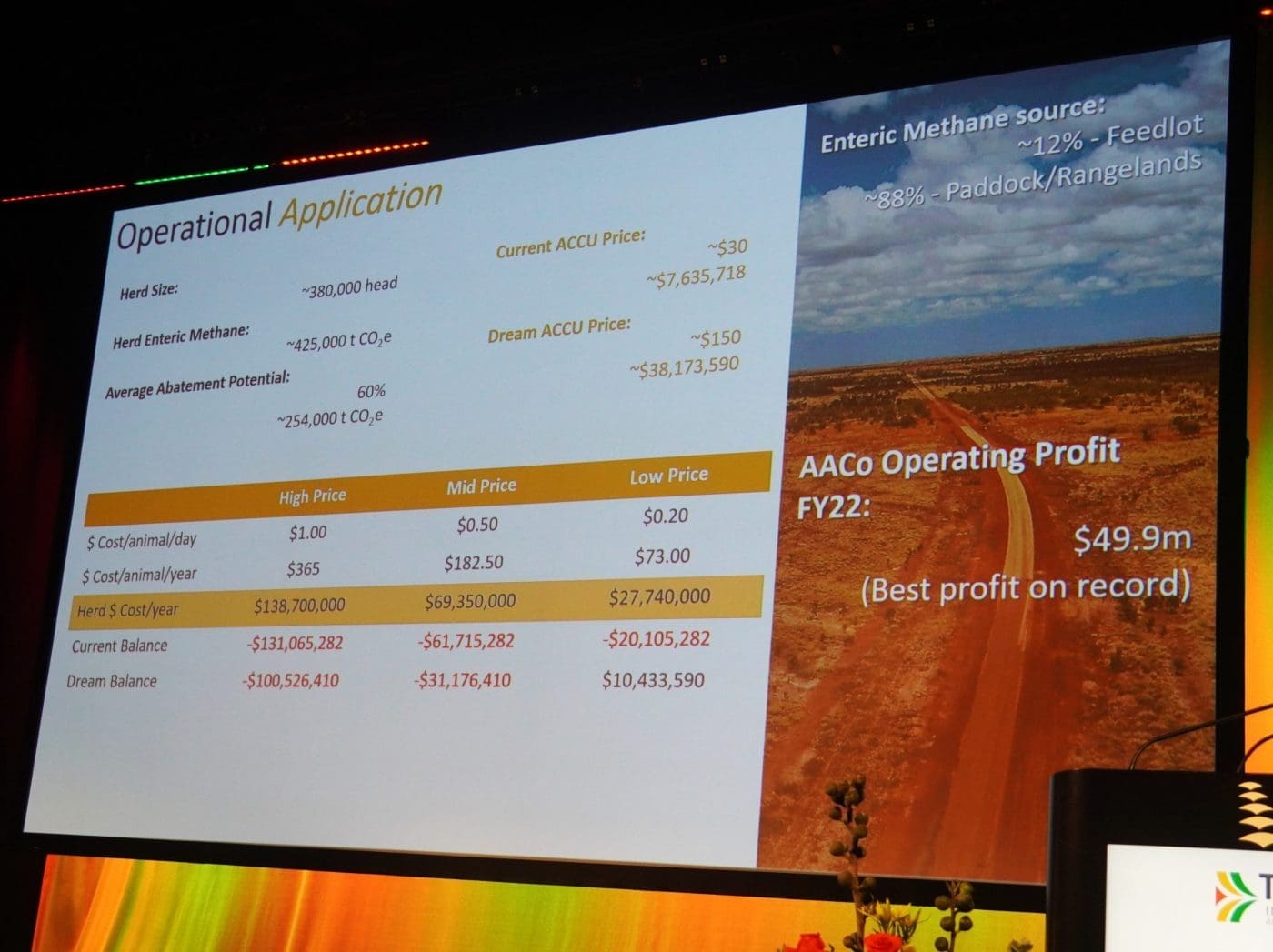

Of the 84pc of AA Co’s carbon emissions currently generated from enteric methane, only about 12pc of that occurred in the feedlot, with the remaining 88pc in the paddock, the audience was told.

“Getting the asparagopsis product out of the feedlot and into the paddock is going to be a significant challenge,” Ms Wilson said.

But even if the company can solve the technical issues, the economics also came into the equation.

“Where we’re at today, AA Co has about 380,000 cattle, producing around 425,000 tonnes of carbon a year. If we could solve the technical problems and abate 60pc of that a year, what’s that going to cost us?” she asked.

Ms Wilson presented the following table, which set out costs based on two scenarios – a current ACCU price around $30/tonne, and a ‘dream’ ACCU price of $150/t (there was lots of modelling that suggested ACCU prices might rise through the roof, over time, she said).

“If AA Co could sell that 60pc carbon abatement through ACCU’s at the current price, it would generate around $7.6 million a year. At the ‘dream’ ACCU price, it would be about $38 million,” she said.

However the cost-per-day to feed the additive in the paddock was the challenge. Using ‘indicative’ prices of $1/head/day, 50c/head/day and 20c/head, the table shows a cost per head over a one-year cycle of $365, $182, and $73 for the three price levels.

Apply that across 380,000 cattle for a 60pc abatement, and the annual cost is significant, to say the least. At $1/head/day, it would amount to $138 million, and even at the lowest price of 20c/kg, almost $28 million.

“Put that in the context of AA Co’s operating profit. Last year we logged our best-ever operating profit, of $49.9 million,” Ms Wilson said.

“So if we are feeding at $1 a day to 380,000 head, and selling the credits to generate ACCUs, we are not going to come anywhere close to breaking even – a loss of $131m on current balance and $100m on the ‘dream’ balance,” she said.

“It’s not an economically viable solution for us at this point in time. Even at the lowest feed cost of 20c/day, and with a dream price of $150/ACCU, we’d just get a cross the line, making a $10m profit.”

But once those ACCU’s are sold, AA Co would still have its emissions profile to deal with.

“We haven’t actually solved the initial problem,” Ms Wilson said. “As you can see, there’s a lot of work to do.”

She suggested there was a number of angles the industry needed to focus on.

“We need to develop a suite of methane mitigants and abatement tools – not just feed additives, but an integrated approach to how the industry deals with methane,” she said.

“For example, I’d like us to have a look at bio-genic carbon – but that’s a chat for another day.”

Questions

During questiontime, Ms Wilson was asked how long ago AA Co developed the concept of climate action.

“We talk about sustainability in AA Co as something that we are on a journey over. Seven years ago, it was a completely different company in this space. We’ve done a lot of really hard work, and done it really fast, to recognise the challenges in front of us.

“We talk about sustainability in AA Co as something that we are on a journey over. Seven years ago, it was a completely different company in this space. We’ve done a lot of really hard work, and done it really fast, to recognise the challenges in front of us.

“One of the features that has really helped us to get there is the fact that AA Co is publicly listed, and there is a clear expectation in the stock market that we do take action in this area. There are reporting frameworks that drive expectations for ASX listed companies to allow them to report on their impacts on climate and nature, the risks to the business associated with those, and to then take action.

“Having that as a driving factor has really helped us accelerate our culture around sustainability – to the point of being able to reach a commitment to take climate action.”

How does a large organisation like AA Co actually prepared for climate change, like greater heat stress events? another conference attendee asked.

“The first step is to understand what that impact actually is,” Ms Wilson said. “We have undertaken our first climate risk assessment – it’s a weighty document, and it can be found in the annual sustainability report, including what we’re doing to address that.”

“It’s things like bringing in more sustainable stocking models, being more-pro-active in understanding the capacity of the landscape that we’re working in, and giving that landscape the ability to have some buffer.”

“There’s a lot of work we’re doing in better understanding that landscape function, and how it is changing over time, and how that connects with the productivity of our business.”