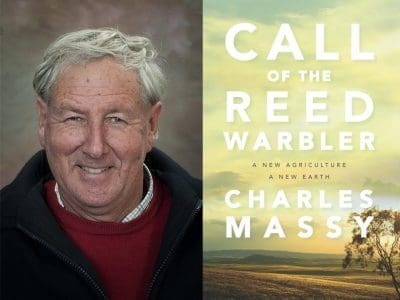

Charles Massy addresses an RCS Forum at Beef 2018 in Rockhampton last month.

NSW farmer, scientist and author Charles Massy interviewed more than 150 farmers across Australia who practice regenerative agriculture, many of whose stories are recounted in his recently released book The Call of the Reed Warbler.

The book also documents Charles’ own self-described “mistake ridden journey” as a farmer, one that started with what he terms as the industrial agricultural paradigm of treating nature as the enemy before moving to ‘ecological literacy’ – in effect understanding how to read landscapes and simply how to “get out of mother nature’s way”.

This is not a story of locking up country but of farmers demonstrating how through learning to work with nature instead of against it, they have not only improved environmental outcomes, but more productive and profitable business outcomes as well.

This is not a story of locking up country but of farmers demonstrating how through learning to work with nature instead of against it, they have not only improved environmental outcomes, but more productive and profitable business outcomes as well.

When his father died at an early age, Charles, having completed a Bachelor of Science degree at ANU in Canberra, returned to take over the family Merino and cattle property near Cooma at just 22.

“If you want an expert on making mistakes I am the expert,” he told a room full of fellow livestock producers at an RCS-hosted forum at Beef 2018 in Rockhampton last month.

“I have set-stocked, over grazed country, watched it turn red in the 80s drought, watched it get washed away etc.

“And yet I was always keen on nature so I was at tension with myself.”

His story is one of self-deprecation rather than pulpit lecturing, a sharing of lessons learned from 40 years of closely observing the landscape as a farmer and a scientist, which included returning to ANU to complete a PHD in human ecology in 2009.

As a 22-year-old taking over the farm he said he sought the advice of other farmers and departmental experts, but after making mistakes he began to realise that his problem was one of “lanscape illiteracy”, in that he wasn’t able to read and understand and in turn effectively manage his own landscape.

He delved more deeply into history, and the land management role played by the first white settlers to Australia who came from northern Europe, a very different and young land with post-glacial, humid soils ‘chock full of nutrients’.

“They hit this extraordinary and ancient landscape of ours, soils heavily leached over time, phosphorous in incredibly minute amounts, a landscape that over tens of millions of years had evolved remarkable ways of recycling scarce nutrients whether it is microbially under the soil or for energy and nutrients above the soil.

‘Europeans came with a different mind and in a very short time the landscape collapsed’

“So these Europeans came with a different mind and in a very short time the landscape collapsed.”

In contrast to the ‘organic mind’ of indigenous cultures, who saw themselves as inherently part of nature and its cycles, not separate from it, Europeans that arrived in Australia with a ‘mechanical mind’ shaped by the industrial revolution, through which they saw the earth as a resource for extracting for profit.

“It is a huge mind shift, and there was no empathy or understanding that came with that mind,” Mr Massy said. “The current industrial paradigm (is one in which) we see nature as the enemy to be dominated.”

It is only in the last 10 years, he says, that thousands of scientists around the world have put together a more complete picture of the earth’s systems and how they interact.

Industrial agriculture has been implicated in destabilising seven of those eight systems.

But counter to that is significant evidence that regenerative agriculture offers the best of all solutions to turn around those Anthropocene problems.

A key message was that “you can’t fool around and interfere with one cycle without all the other ones being destabilised”.

Turning it around involves increasing ground cover and nutrient rich shrubs to get “as many solar panels on our landscape for as long as we can, to pass those sugars into the soil to build the carbon to feed the bugs and to bury those long-term carbon polymers”.

He offered several case studies to demonstrate how quickly things can be turned around – examples of country that was previously bare and flint-hard after over a century of set stocking transformed in 10 years to regenerated grassland with soft and absorbent soils, a greater variety of shrubs “which have thousands of additional nutrients in them”, collectively maximising the ‘solar panels’ on the landscape.

He offered several case studies to demonstrate how quickly things can be turned around – examples of country that was previously bare and flint-hard after over a century of set stocking transformed in 10 years to regenerated grassland with soft and absorbent soils, a greater variety of shrubs “which have thousands of additional nutrients in them”, collectively maximising the ‘solar panels’ on the landscape.

“Once you drive the solar you get a deeper-rooted variety of plants, more air pockets, more active soil biology, and it leads to an enormous increase in water holding,” he explained.

Several pictures demonstrated the “fence line effect”, one showing the result of three inches of rain in two hours on two neighbouring paddocks – on the set-stocked paddock the water is pouring off, on the holistically managed paddock it is all being absorbed into the soil.

“If you think about it, here we are on the driest continent on earth, where we often get hard rainfalls, and in 24 hours one neighbour triples his effective rainfall.

“It is all pretty profound stuff.”

Mr Massy said these results have been achieved in “incredibly tough” seven to ten-inch rainfall areas in Australia and South Africa and Mexico, where graziers have been able to triple their production essentially by increasing groundcover and shrubs.

One farm revegetated and measured by an ex-CSIRO scientist near Canberra for the past 30 years has been shown to have sequestered 11 times more soil carbon than its total farmed emissions in that period, and has moved soil carbon levels from one to four percent in the same time.

“A lot of the research now into these cycles shows that if we can just put one percent more carbon into the soil we can store an extra more than 140,000 litres of water per hectare just by doing it.”

Mr Massy said that with returning to scientific study after 30 years came an understanding of complex adaptive systems – earth systems, water catchments, even the world wide web – which if destabilised have a capacity because of their complexity to adjust and ‘self-organise’ back to health.

“This concept of self-organisation in natural systems and even the world wide web have an in-built capacity if they’re destabilised or if there is a new factor such as a drought or change in management, to reorganise if allowed to reorganise back to health and resilience.

“And to me that is an extraordinary new concept.

‘I keep meeting these leading regenerative farmers who say ‘my job is to get out of the way of mother nature’

“I keep meeting these leading regenerative farmers who say ‘my job is to get out of the way of mother nature’.

“I have thought have about that and my job is to let natural systems self-organise back to a better state, and I think that is an extremely exciting concept.”

Mr Massy said humans evolved on the savannah eating meat and food produced from a nutrient rich landscape, but nutrient levels in modern cereals, fruits and vegetables had crashed, and chemicals such as glyphosate had infiltrated food, water and soils.

“We evolved to have a diversity of nutrients, where is all the modern disease coming from, particularly the immune stuff? These are the big factors,” he said.

“Hippocrates 2500 years ago said “let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food.

“…There is a lot stuff now coming out to show (Glyphosate) is probably the most dangerous chemical in our environment… personally I think this is bigger than tobacco”.

Mr Massy said he interviewed over 150 regenerative farmers across Australia to understand why they had undertaken a paradigm shift from traditional farming to regenerative farming. Their stories are shared in his book “the Call of the Reed Warbler” – the title a reference to the return of the native bird to his property after a long absence.

Mr Massy said the urgent challenge is to “go beyond” sustainability.

“I use that word because I think the word sustainable is a bit passé, to me it means marking time, whereas regenerative means open ended improvement, and the only way as I see it, the response is to get ecological literacy.

“We have destabilised the systems through industrial agriculture but regenerative agriculture more than anything else going has the potential to start turning around those Anthropocene problems.

“That is an extraordinary and powerful and exciting thing I would have thought.”