Winter coats are often associated with dag buildup on feedlot cattle, which costs time and money to remove before processing

THE ability of cattle to adapt to environmental challenges is one of the major considerations for producers across the nation. In many cases adaptability is only thought about in broad terms, where an environment may be classified as temperate or tropical, rangeland or coastal.

Consequently, many of the decisions made to select stock for adaptability are often broad and generic.

Adaptability to heat, particularly where humidity also is a feature has often seen producers move to utilise genetics from breeds that are proven to have tolerance to these conditions.

While hot and humid conditions are a feature of northern production environments, southern production regions also face significant challenges with summer heat. In many of these areas the use of Bos Indicus genetics may not be practical or necessarily appropriate for these regions.

Within the British and European breeds commonly run throughout southern regions, there is wide variation in heat tolerance and overall adaptability. This variation has been a focus of work in the United States where many production environments face similar environmental challenges to temperate regions of Australia.

In work published by the University of Missouri, it has been shown that the amount of winter coat shed by a set date during spring or summer is a very effective predictor of an animal’s ability to cope with heat stress.

While hair shedding is often an indicator of other factors that include nutrition or health status, early shedding is a very strong indicator of adaption to a production environment, the research shows.

Heritability

In addition, the research has shown hair shedding is likely to have a direct effect on heat loss and has been correlated with improved productivity in the cow herd. Notably, the work that has been published so far shows that hair shedding is a highly heritable trait, offering opportunity for producers to select for animals that shed winter coats earlier in spring and summer. The work has also shown in British breeds to have a positive relationship with growth rate.

In a presentation to the US Beef Improvement Federation, Drs Jared Decker and Jamie Courter outlined some of these findings. Importantly they noted that there is a genetic difference between coat type and hair shedding.

In a presentation to the US Beef Improvement Federation, Drs Jared Decker and Jamie Courter outlined some of these findings. Importantly they noted that there is a genetic difference between coat type and hair shedding.

Dr Courter emphasised in her presentation that the gene for a slick coat (short fine hair) is a different gene to that which influences the time in which an animal sheds its winter coat.

In explaining the impact of hair shedding, Dr Decker illustrated the impact increasing day length has on animals and the genetic response that triggers hair shedding.

Increased day length triggers the hormonal response for an animal to decrease production of melatonin. Reducing melatonin allows the animal to increase the production of prolactin, which triggers seasonal hair shedding.

In effect, hair shedding is an indication of animals that are more responsive to daylight changes – effectively responding or adapting more quickly to their environment.

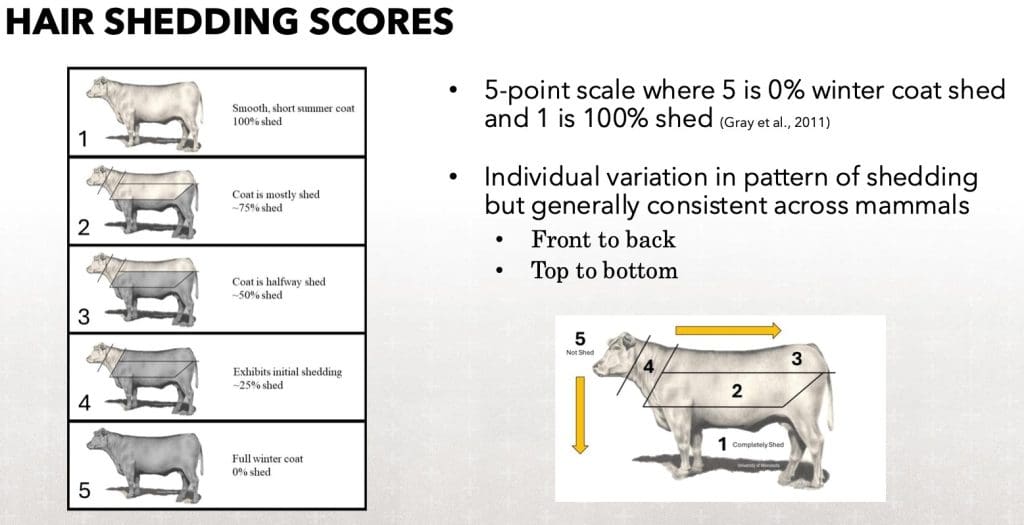

The work published in the US offers a guide to scoring hair shedding in cattle from a score of 1 – 5. Score 1 is given to cattle that have shed their entire winter coat and have their “slick” summer growth, through to 5 where cattle have yet to shed any winter hair.

It is recommended that producers who see value in selecting cattle that shed hair earlier use this simple scoring system. However, as with any selection process it is important to be consistent and assess all cattle at the same time.

Australian research into hair shedding was conducted by the CSIRO during the 1960s. In a paper published by R.H Hayman & T. Nay, they found that cattle could take up to four months to completely change from a winter to summer coat, but that the majority of shedding occurs during September in southern areas.

This research also suggested that Bos Taurus cattle grazed in semi tropical areas would commence shedding their winter coats 10-12 weeks after the winter solstice, but in temperate areas shedding could start earlier, at 5-10 weeks.

For Bos Indicus breeds, the 1960s research suggests hair shedding would start 5-6 weeks after the winter solstice. The CSIRO researchers also suggested day length was a major contributor to hair shedding. The paper highlighted the importance of selection on shedding as being “valuable in producing animals adapted to hot environments”.

In practical terms, while producers may be seeking to breed cattle with finer or ‘slicker’ coats, particularly with feedlot markets in mind where dag buildup on coats can become a major problem, hair shedding is a separate trait and one of equal value.

Selecting animals from within a herd and a breed that can respond to seasonal conditions earlier may offer some advantages in both production and for overall livestock welfare.

Alastair Rayner is the General Manager of Extension & Operations with Cibo Labs and Principal of RaynerAg. Alastair has over 28 years’ experience advising beef producers & graziers across Australia. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au

Alastair Rayner is the General Manager of Extension & Operations with Cibo Labs and Principal of RaynerAg. Alastair has over 28 years’ experience advising beef producers & graziers across Australia. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au