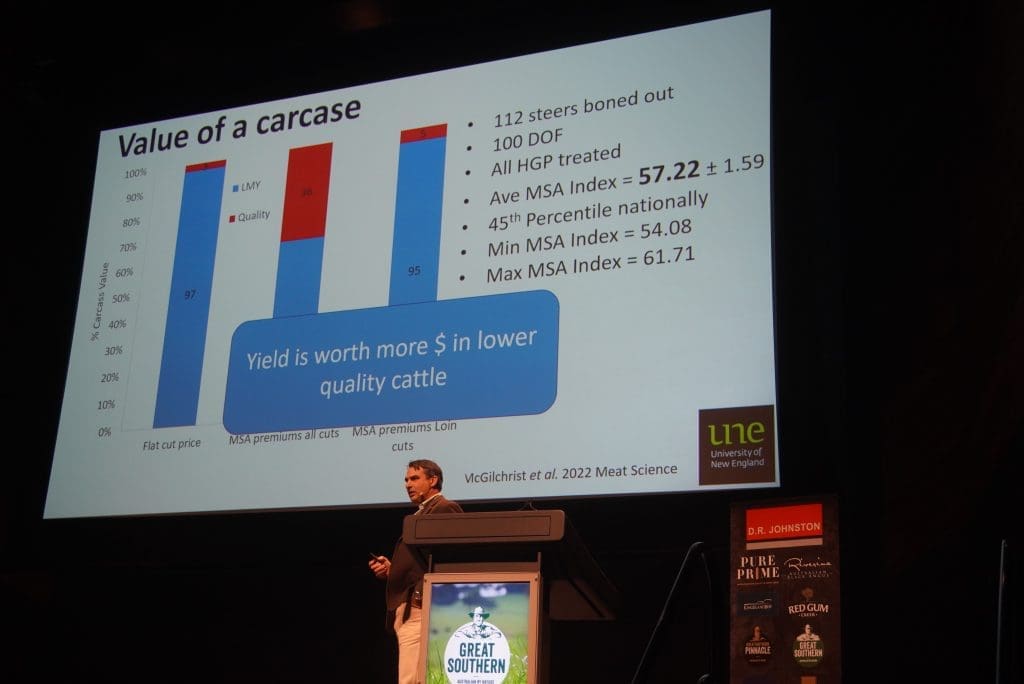

Dr Peter McGilchrist addresses last Friday’s JBS Great Southern supplier conference

THE beef industry’s growing focus on sustainability and methane footprint will contribute to greater emphasis in genetic selection on cattle with superior meat yield and growth rate.

That was one of the messages from meat scientist Peter McGilchrist, delivering a presentation at JBS’s Great Southern beef and lamb supplier conference in Melbourne last Friday.

Dr McGilchrist, from the University of New England, focussed on the elements that deliver real carcase value, suggesting the industry had been “ignoring carcase yield for bloody decades,” to its disadvantage.

He said before anything else, the cattle a producer needed to breed efficient animals.

“What drives value out of our carcases? It’s actually pretty simple – it’s the quantity of saleable meat (how many kilos can be harvested off the carcase and into a box or a cryovac pack) multiplied by the quality of the meat,” he said.

In research work he co-authored last year with Dr John Thompson looking at the value of beef carcases, Dr McGilchrist said a research project boned out 112 typical steers fed 100 days and given a typical implant program.

They produced an MSA index around average for this type of animal, of 57.22, in the top 45pc nationally for all MSA graded animals.

“If we had put all those carcases in the same box, with no differentiation on good, better and best, yield would have driven 97 percent of their value,” Dr McGilchrist said.

If all of the cuts harvested were sold for their premium quality (five star at double the price of three star, for example – remembering the research cohort were only MSA index score 57 animals, on average), quality still only drove 36pc of the value in those trial carcases.

“It was bigger, but not too much,” Dr McGilchrist said.

“If we had only sold the rump, cube roll, striploin and tenderloin for premium prices, based on tenderness, and sold the rest as commodity beef, yield drove 95pc of the value of the carcase,” he said.

The key message in this was that yield was worth “way more dollars” in lower quality cattle than quality.

In a second part of the project, HGPs were removed, pushing the average MSA Index in the cattle to 62 – roughly equivalent to JBS’s large Great Southern Pinnacle (marbling score 2 or better) range.

“Even in those superior performing cattle, if we don’t sell them into brands, yield still drives 97pc of the value of those HGP-free carcases. But if we were to sell them all into brands, like Great Southern, Pinnacle and Little Joe (used as examples for this specific producer audience) quality all of a sudden drives 70pc of the carcase value,” Dr McGilchrist said.

“Because you (JBS Great Southern cattle suppliers) produce amazing animals, quality does drive a lot more of the value of each carcase. But even in these elite performers, yield performance still drives 30pc of the value.”

If only the top four loin cuts were sold at a premium as good, better and best, quality still only accounted for 12pc of the carcase value, Dr McGilchrist said.

This point was reinforced earlier in the seminar when JBS’s Sam McConnell stressed the importance of extracting premiums for all parts of a Great Southern carcase – including trim, which made up 25pc of saleable meat – to offset the production cost under the farm assured program.

“It’s an interesting piece of work,” Dr McGilchrist said about the research project. “Quality is worth more dollars in higher quality cattle – provided all the cuts are marketed on a quality basis.”

Ignoring yield for decades, as sustainability imperative grows

Dr McGilchrist told the producer audience he thought the Australian beef industry had been “ignoring the importance of yield for bloody decades.”

“I’m a bit fired up about it,” he said.

To lay down a kilogram of fat, an animal had to eat six times the amount of grass it took to lay down a kilo of muscle.

“Is that efficient? Not really. So we have to get requisite fat in the right depots on those animals so they’re both efficient, and grow fast. That means the fat in the marbling depot.”

The industry did not get paid a lot at the moment for producing more efficient animals – but it was coming, Dr McGilchrist suggested.

“With the entire industry’s aspirations towards Carbon Neutral by 2030 (CN30) and moderating methane, efficiency of our production system becomes increasingly important. And number of days to slaughter weight is one of the biggest drivers of methane production,” he said.

“If we can get more cattle to market weight earlier, while having fat in the right depots, they are going to be the animals we want.”

Cattle producers currently got paid on carcase weight – not dressing percentage (the difference between live weight and the dressed carcase weight). And that value flowed along the carcase chain. However there were also dangers in chasing yield (or growth) at the expense of meat quality.

The lamb industry had seen a gradual decline in eating quality for the past 15 years, as the selection emphasis shifted to growth. But lamb (apart from maternals/Merinos) was now starting to turn the corner in terms of eating quality.

Dr McGilchrist said some beef breeds had a retail beef yield Estimated Breeding Value, but little attention had been focussed on it over the years, in terms of selection.

That was primarily because there was little sign of any financial incentive in terms of payment for better yielding carcases.

There was not a lot of data yet, underpinning the yield EBV, so it had been increasing over the past few years.

Asked whether there was a risk of beef going down the lamb path and damaging meat quality in any greater genetic pursuit of yield/growth, Dr McGilchrist thought not, because the two traits were not strongly correlated.

“They were very correlated when we did not measure both of them. But now that we are measuring them separately (see references below), we are trying to find those ‘curve benders’ that carry both meat quality and greater efficiency, in terms of yield.

“If we can find progeny of sires that give us both, we are really onto something. But if we don’t measure anything, we will never find them.”

The bulls that currently made a lot of money were those curve-benders (low birthweights, heavy growth to 400 days, moderate mature size by high IMF). But so far there had not been a lot of negative pressure on rib and rump fat.

“We know fat’s important for an animal’s resilience, getting through dry periods on sub-optimal nutrition. So there’s an amount of external fat that’s needed in the system, meaning we can’t select for ‘really negative’ fat.

“But those bulls that are making really big money are increasingly those that are high in IMF, and not very high in rib and rump fat,” Dr McGilchrist said.

“Bull breeders are chasing that growth/eating quality combination more now, but are not really chasing that growth/yield combination, because there’s still no market incentive (ie grid price consideration) for it.”

“But I think the big kicker for yield selection will come in this big-picture efficiency/sustainability space.”

“As I said earlier, it is six times less efficient to lay down a kilo of fat, as it is a kilo of meat. In the domestic market, for example, those young animals need just enough fat to give a good eating experience – but really, their eating quality comes through inherent tenderness in young animals – not marbling. The whole domestic industry could go to a very young, very efficient animal – getting to a market weight in the shortest amount of days.”

“It will be this sustainability imperative that pushes yield along – more than anything else.”

“Once everyone has a focus on kilos of beef produced per kilo of grass grown per mm of rainfall, and we are measuring carbon and sustainability, I think it’s then that these animals which are higher yielding while still delivering meat quality will rise to the top.”

“Those results can them be driven through sustainability claims in brand programs and the broader industry.”

Emerging measurement tools

So how does the industry currently measure carcase yield? Producers may get it through carcase feedback (JBS was one of the only companies that did that, Dr McGilchrist said) based on a calculation using rib fat and carcase weight.

While the accuracy of the algorithm it relied on was very poor, the industry ‘accepted it.’ But there were processes being examined under the Advanced Measurement Technologies (ALMTech) program that could see better methods to measure yield on an individual carcase basis.

Just some of these technologies included VIAscan, E+V, Frontmatic, UTS and DEXA systems (see earlier Beef Central stories, including this one).

“We’ve come a little bit of the way over the past seven years through the ALMTech work, but this tech needs ongoing investment, development and adoption right across the industry if we are going to move our industry-wide yields and efficiencies anywhere in the coming decade,” Dr McGilchrist said.

“The beauty of these camera-based and other technologies is repeatability. They can produce scores from camera to camera, and from plant to plant, and from one week to the next about 30pc higher (in consistency) than human assessment.

Humans are our current system, and they do a great job, but these technologies are going to be an awesome aid in helping increase that repeatability, meaning greater consistency in our brand programs. That commercial roll-out takes time, but it is our current challenge in getting the systems into company plants and getting them used.”

Role of feed additives in methane reduction?

During questiontime, Great Southern seminar speakers were asked about the future of methane-reducing compounds like asparagopsis and Bovaer to mitigate the industry’s environmental footprint.

Jason Weller JBS chief sustainability officer

JBS’s global sustainability officer Jason Weller, participating via video-link, also identified the role more efficient cattle would have in methane inhibition and more sustainable beef production.

“JBS has been doing large scale trials of different additives in Brazil,” Mr Weller said.

“While promising tools, our view on their use is a little more measured,” he said.

“We believe there are other ways to address enteric emissions in cattle. Enteric emissions (as opposed to emissions from grazing systems or manure) is going to be one of the most challenging components to tackle.”

Nobody had yet quite figured out how to actually get the additives into the animal’s diet, Mr Weller said.

“They have been documented to work well in feedlot situations, but depending on the production model and the country involved, relatively few cattle may go through a feedlot program. In Brazil, for example, 65pc are exclusively grassfed. Even in the US, which is heavily reliant on feedlots, the great majority of an animal’s lifetime enteric emissions happen before it enters the feedlot,” he said.

“So I, personally, am a little more hesitant on the near-term solution around these feed additives.

“Instead we are interested in other ways to start addressing emissions intensity in cattle. This can include breed, genetics (even within breeds, different animals will have significantly different enteric emissions) and animal scientists are just now starting to focus on the genetic component, also age at slaughter.”

“If we look at the total enteric emissions volume of an animal over its lifespan, the quicker that animal can be brought to market, while still producing a quality product, the better, in terms of enteric emissions,” Mr Weller said.

“The short answer is that there are a lot of ways we can near-term control total enteric and greenhouse gas emissions, and emerging animal science and productivity gains will be part of that. And in certain environments like feedlots, some of those additive solutions may play a part in the medium term.

“But there’s not going to be any one silver bullet. When you look at a comprehensive systems approach, we’re going to have a number of different tools and levers that producers can use to address enteric emissions.”