NSW seedstock producer Sally White from Eastern Plains near Glen Innes expresses her opinions about the value of semen morphology testing, and offers some compelling reasons why it is not more widely adopted …

The fundamental job of a breeding bull is to get females in calf. He’ll generate more profit, if he does this earlier in the breeding season. If the bull has an inherent fertility problem, meaning he is infertile or sub-fertile, he will not be able to do this.

Though a bull may present fat and sappy on bull sale day, with tremendous phenotype & genotype, it’s worth noting that this has no relationship whatsoever with his fertility or reproductive function.

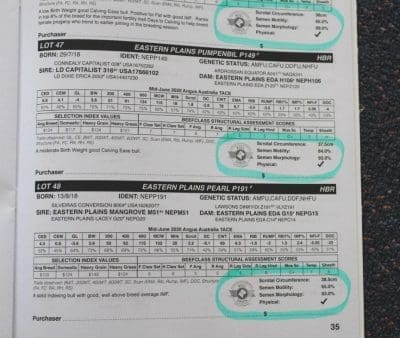

So on bull sale day, how can I tell if a bull is fertile, infertile or sub-fertile? The answer is simple, but little applied. Pre-sale sperm morphology testing bulls, prior to their entry into a sale ring, is the best means to accurately identify infertile and sub-fertile bulls. It is a long established, objective measurement of bull fertility.

But even though it’s fundamental to the job of a bull – and thus, profit – it’s no easy task to buy bulls at auction out of a sale ring, with sperm morphology test results. Why is this?

To begin, what is sperm morphology?

Sperm morphology describes the anatomy or structure of individual sperm cells. It cannot be tested ‘crush side’.

Testing for sperm morphology requires a large, specialised laboratory microscope to examine a preserved semen sample to assess the integrity of the sperm head and tail. Test results are expressed as the percentage of normal sperm cells in a semen sample or percent normal sperm (PNS).

The percentage of abnormal sperm cells is also reported, classified into seven categories. It’s highly likely these abnormal sperm cells will prevent conception.

Though they may make it to the site of fertilisation, the resultant embryo will be non-viable and unable to be maintained. So the female will fail to conceive on that cycle, falling into a later calving round.

The recognised minimum standard for bull fertility in Australia is greater than 70pc normal sperm for bulls used in single sire mating or AI, and greater than 50pc normal sperm for bulls used in multiple sire mating.

Sperm morphology should be not be confused with sperm motility or “crush-side semen testing.” Sperm motility testing determines whether the sperm are progressively forwardly motile. That is, are the sperm alive and swimming ‘forward’, which is obviously important to achieve fertilisation.

Motility of the sperm is also expressed as a percentage. The recognised minimum standard for bull fertility in Australia is greater than 30pc progressively motile sperm.

A bull may pass one but fail the other. However a bull needs to pass both to demonstrate that he is truly ‘reproductively sound’. In so doing, he demonstrates he has a high probability of being fertile as opposed to infertile or sub-fertile. He demonstrates he is ‘road worthy’ & ‘fit for purpose’ – that is, breeding.

Bull sale catalogue claims

Too often we bull buyers read in a bull sale catalogue, “All bulls have been semen tested”, yet actual results are not disclosed. Moreover, if you ask the direct question, it is too common that “semen tested” reveals bulls have been crush side tested only (for sperm motility). They have not been tested for sperm morphology as well.

Without both sperm motility and sperm morphology testing, you’re no further ahead in being able to identify a bull with an inherent fertility problem.

One to two in five, are duds

Alarmingly between 20pc and 40pc* of bulls will fail a sperm morphology test, depending on breed.

Of utmost importance to the bull buyer is that those who fail are at worst infertile, and at best, sub-fertile.

So for those buying bulls out of a sale ring, where the bulls have not been sperm morphology tested, about one in five (more depending on breed) will likely turn out infertile or sub-fertile, with an inherent fertility problem.

So for those buying bulls out of a sale ring, where the bulls have not been sperm morphology tested, about one in five (more depending on breed) will likely turn out infertile or sub-fertile, with an inherent fertility problem.

Depending on the timing of the joining program, the cost of buying an untested bull with an inherent fertility problem may not reveal itself until up to a year after his purchase. Too often, they fly under the radar but at a cost borne by the bull buyer. This cost lies in a higher incidence of preg-tested empty females or females calving late in the breeding season.

Buyers may have observed bulls with fertility problems serving females during the joining season, and understandably, think all is well.

In a multiple sire mating in a joining program it can be almost impossible to identify an infertile or sub-fertile bull (without sperm morphology testing) as other bulls may cover for him to some extent. This extra workload for the remaining (fertile) bulls makes it more likely they may incur an injury during the joining season.

Yet more cost to bear.

A sub-fertile bull may still sire calves, but they’ll likely be costly, late calves as his sub-fertility can result in a non-viable embryo so that the female will fail to fall in calf on that cycle.

Thus she falls into a later calving round, producing a later, less profitable calf. It is difficult for the female to then break out of this late calving cycle, increasing her chances of PTE in a subsequent joining.

So it’s more probable she will end up culled from the breeding herd, though the fertility issue was never of her making. Rather its source was sub-fertility in the bull.

Why the poor uptake in morphology testing?

So why the poor uptake in pre-sale sperm morphology testing? Does it cost too much? Is there a lack of understanding? Don’t bull buyers care? Is it a question of integrity in the seedstock industry?

All of these are likely reasons, and often more. But I’d like to comment on a few ‘reasons’ that seem often used to argue ‘against’ pre-sale testing.

Firstly the cost of sperm morphology testing is very economical – $35/head at most. The major cost lies more in the direct cost to seedstock producers of culling those bulls who fail sperm morphology testing from their sale drafts.

If sold through the sale ring in the current market, a bull may fetch$8000/$9000, but if sold for slaughter because he has tested infertile or subfertile, he is worth about $2000/$3000.

Most likely this is the sticking point, in my opinion. But really, when buying bulls at auction out of a sale ring, it is fair and reasonable to expect them to be reproductively sound and fit for breeding purposes, at the fall of the hammer. If not, then this is a cost that should rightly be borne by the seedstock producer, rather than the bull buyer.

Even though many seedstock vendors offer clients a credit at a future sale for bulls that may subsequently fail a ‘vet test’, the bull buyer will have already borne the cost of lost production by the time this eventuates.

What’s more, the buyer’s credit could well be used to buy another bull with an inherent fertility problem, if that seedstock vendor continues on the path of not testing sperm morphology & sperm motility.

Secondly, a common catch cry is that ‘sperm morphology varies over time’ so ‘don’t hang your hat on a single test result’. This is 100pc true. Just like any other raw measurement, such as weight and eye muscle area, sperm morphology is not a constant and will change.

Sickness, disease, injury, environment, nutrition or indeed any stress arising from a production system or husbandry program (such as vaccinations) can impact on sperm morphology.

Once sexually mature, a bull is continuously producing semen throughout his life. From start to finish, when semen is ready for ejaculation, takes a production period of about 6-8 weeks. Taking this time period into account, once the bull recovers from a stress event, his sperm morphology will similarly recover, providing he does not have an inherent fertility problem.

While a subsequent test result may vary from a former, ‘good’ sperm morphology has been shown to be repeatable in a reproductively-sound bull which is without an inherent fertility problem.

Varying results from lab to lab?

Thirdly, some argue that as sperm morphology test results can vary from laboratory to laboratory, they cannot be considered a reliable indicator of bull fertility.

While results can vary by laboratory, this can be mitigated. If testing is carried out at labs with comparable equipment (some brands of microscope are better at detecting abnormalities in the sperm than others), staff are of equivalent competency (is the morphologist experienced, qualified & trained, doing this kind of work on a daily basis) and if results are reported in the standardised format according to the national guidelines for classifying sperm abnormalities, it’s unlikely the variation in results between labs will be so substantial as to render them null and void.

The reality is a sperm morphology test result is not a guarantee for fertility in the bull, as there are so many factors that can either permanently or temporarily affect bull fertility.

But this in no way discredits sperm morphology as a reliable, accurate measure of bull fertility. Pre-sale sperm morphology testing of bulls will weed out the true losers when it comes to fertility which crush side semen testing on its own will not.

These bulls do not belong in a sale ring. Pre-sale sperm morphology testing is the best means currently available to substantiate that those bulls entering that sale ring have a high probability of being fertile, do not possess an inherent fertility problem (that will not correct itself over time), and are not infertile or sub-fertile.

Multiple industry funded, published, formal, peer reviewed, scientific research papers stand behind this claim. It is not a smoke and mirrors ‘marketing tactic’ or subjective opinion.

Surely this is ‘bread & butter’ stuff for bull buyers & the seedstock industry? The lack of widespread uptake is a continuing industry wide cost though there is a means to readily address it.

So in future, I encourage bull buyers to ask the specific question of their seedstock producers: “Are sperm morphology results available for these sale bulls? If not, then why not?”

Be proactive and have the conversation. You’ve much to gain.

*Felton-Taylor, Prosser, Macrossan, Perry (Theriogenology 2020)