THE purpose of this report is to focus on the events that directly impact Australia’s beef as a result of the recent tariff war that has erupted between the US and China.

To me, the potential impact falls into two areas: The micro-impact on China demand and in particular, chilled grainfed beef; and the macro-impact of more protein, due to displacement of US pork exports to China and potentially the impact on the US market domestically and other export markets which in turn impacts Australian export beef pricing.

To me, the potential impact falls into two areas: The micro-impact on China demand and in particular, chilled grainfed beef; and the macro-impact of more protein, due to displacement of US pork exports to China and potentially the impact on the US market domestically and other export markets which in turn impacts Australian export beef pricing.

The following are the key points in this discussion:

- Chinese importers believe the Chinese tariffs on US beef is good for Australian beef, in particular grainfed.

- Chinese consumers will turn to Chinese domestic pork rather than imports.

- The rumour of China and Hong Kong meat inspection services amalgamating continues. which many believe could stop the grey-trade (imports arriving in China from surrounding countries and regions, including Hong Kong and Vietnam, to avoid duties). Some importers argue differently, saying the grey-trade is very difficult to stop.

- Australia dominates 90pc of China’s direct chilled beef trade – although the US was starting to make inroads very quickly.

- MLA in a recent report on China claimed that ‘the average unit price of Australian chilled beef exports to China in 2017 was 21pc above the average of Australia’s combined global markets.’

- MLA’s China report outlines the enormous potential for chilled beef, and in particular chilled grainfed beef, with a forecast 24pc growth over the next four years expected.

- Recent trade data from the US shows that Australian and US beef have been going head-to-head in China since July last year – this was also highlighted by Chinese importers – but with the potential introduction of US beef tariffs, Australia may regain some competitive ground.

- There are 154 beef and sheepmeat establishments approved in total for China across Australia, New Zealand and the US. Within that, 59 are able to export chilled, with the US having 37 eligible chilled plants, Australia 12 and New Zealand 10.

- In recent days Chinese media has talked of the establishment of State Market Regulation Administration (SMRA) which is the combining of AQSIQ and CIQ whose purpose, amongst many roles, is to improve market regulation – in other words control the grey trade.

- The US relies heavily on Hong Kong (proxy for trade with China) with 152,280 tonnes shipped there last year – should an amalgamation occur between the Hong Kong and SMRA as rumoured – this might see a dramatic change in exports to Hong Kong which many countries like the US rely on.

Worth noting at the bottom of this report is a graph and time-line of events that highlights the market impact that has occurred from these events over the last four weeks.

How Chinese importers see the impact on Australian and NZ beef and sheepmeat

I sent a list of questions to several Chinese importers to get their views on the market impact from the introduction of tariffs and the likely trade-flow out comes.

I asked three questions: How has market reacted to the news? Do you think US beef will be impacted? Will we see increased demand for Australian beef?

“Beef has already been impacted,” one importer said. “Yes, it is good news for Australian beef, especially grainfed, because they are competing in the same market. I do not think this will shake the China beef market a lot, as US beef trade is currently quite small (around 700t per month) within China’s total global imports volume of around 60,000t per month.”

I also asked, given reports that domestic Chinese pork and EU imported pork was cheap, whether Chinese were not worried by the tariff, as they could buy elsewhere.

“The US exported around 600,000t of pork and offal to China in year 2017, but only consigned 700t of beef to China in January 2018,” one importer said. “Basically, I agree with you that the US pork business was not a small number, but most of pork consumed in China is still from domestic rather than imported sources.”

I also said I had heard that Chinese authorities might bring the Chinese Mainland inspection agency and the Hong Kong imported inspection agency together, which could stop the ‘grey trade’ happening out of Hong Kong.

One importer said he had heard the same. “But I’m still not sure of the result, as it would not be easy to control the grey-trade in China.”

Australian chilled beef into China

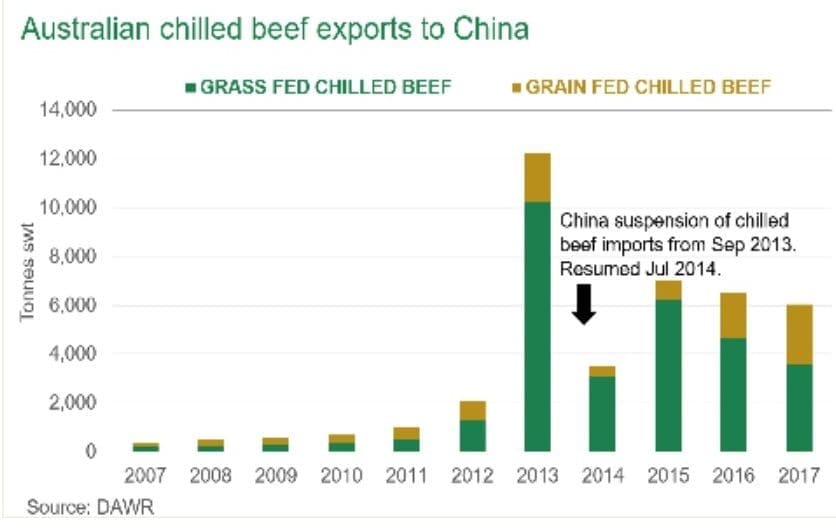

Australia is the main chilled direct beef import supplier to China, supplying 90pc of all imports by volume in 2017. Since 2007 Australia’s chilled shipments has increased from 375t to 6045t (shipped weight in 2017.

In February this year MLA released a report on China, including the following key points:

- China is Australia’s fifth largest chilled beef export market.

- The average unit price of Australian chilled beef exports to China in 2017 was 21pc above the average of Australia’s combined global markets (A$12.94/kg compared to A$10.69/kg) and rose 9pc on the year before, compared to the average of global markets, which was down 1pc.

- Australian chilled beef exports to China comprises 5pc by volume but just over 9pc by value of all beef exports to the country.

- Australian chilled beef is being sold to both high-end restaurants, most of which are independent rather than chained establishments, and premium retail outlets, including e-retail.

- There is a growing gap between China’s domestic production and demand with China relying more and more on imported beef to fill this gap, which BMI Research anticipates will increase by 24pc by 2022 from 865,000t to 1.073mt in four years’ time.

- Chilled meat is currently estimated to make up around 20pc of the market; however, GIRA forecast this to rise sharply to 60–70pc of the market by 2027.

- The reasons given to why an expected shift to chilled beef in preference to frozen and fresh in China include: the government is closing down wet markets in large cities; government policy fostering large-scale meat production and centralised animal slaughter; rising food safety standards; animal disease control and improvements in cold chain plus macro-shifts such as urbanisation; increased disposable incomes; more eating out; and growing acceptance of western-style cuisines.

The following graph highlights the importance of grassfed and the growth of the grainfed sector.

When discussing the MLA report findings with processors in Australia, there was a question-mark over the following statement: “The average unit price of Australian chilled beef exports to China in 2017 was 21pc above the average of Australia’s combined “global markets.”

It was felt that China was a premium market for certain grainfed chilled beef items over Japan and the US, but was still well behind the EU in pricing – the key point being that China offers a premium at the high-end over the majority of global markets on certain beef items (with exception to the EU), and is therefore considered a coveted market by both US and Australian exporters – albeit in small volumes at the moment but with enormous potential.

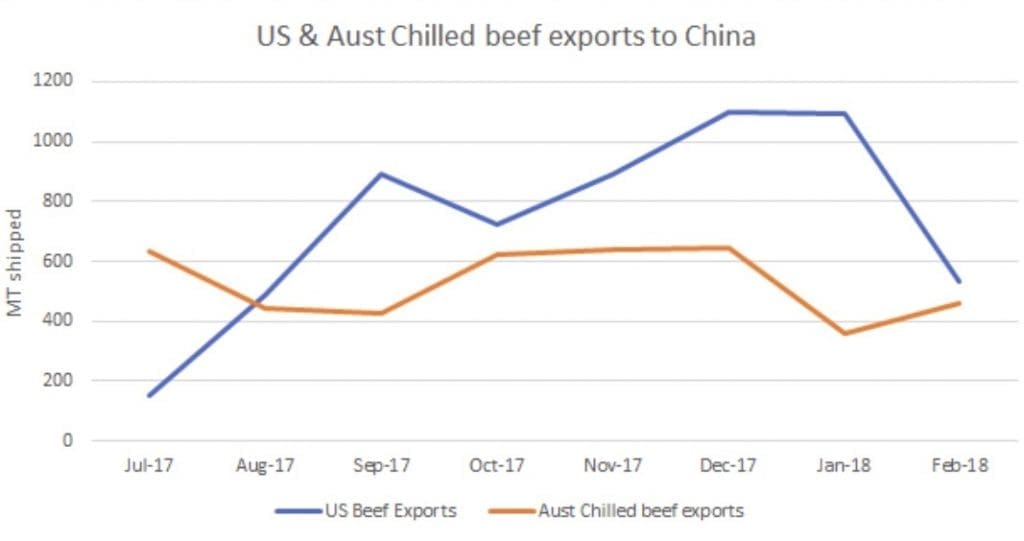

The graph below is based on shipments since July 2017, remembering the US was only given access in June 2017. It confirms and highlights that Australia and the US are competing head-to-head in the chilled beef space, which is the most lucrative chilled space globally at the moment.

When assessing the graph, the October to January period looks to be driven by Chinese New Year demand, and it would seem a preference for US beef starting to occur. It should be noted that seven Australian plants were prevented from shipping to China last year from July to early November, which saw shipments flat-line and opened the window for US beef to build a foot-hold in the market.

“It is the future opportunity cost to US exports that is the key point in the disruption to trade by the Trump administration”

US beef started to outpace Australia from October through to January, even after the ban was lifted on six of the plants, but the fall in February, I believe, is more to do with post Chinese New Year falling demand than customer preference between Australia and US products.

To me, China is a developing premium market, but is still at a very immature stage. But within four years, the BMI Research predicts a 24pc growth, or 208,000t, which is likely to see grainfed chilled beef become a key part of that growth.

It’s no wonder US exporters are disappointed in the disruption to trade that has evolved in the last month due to the Trump administration’s tactics – the US was starting to make serious inroads and no doubt wants to be part of this enormous growth process over the next four years.

It is the future opportunity cost to US exports that is the key point in the disruption to trade by the Trump administration, and even though the grainfed chilled volumes into China are small at the moment, it is the growth over the next 4-10 years that the US do not want to miss out on.

It should be noted that an important market requirement of no HGP’s and traceability since birth are two key China requirements – an estimate I heard last May when the US was given access was only 170,000 head (out of 94.4 million head herd) were eligible. But given the premiums that exist, there is no doubt to me that this figure of eligible cattle has grown since last year.

Australian, NZ and US plants approved for China

The status of Australian, New Zealand and US plants that have access to China is as follows.

Australia’s listings: As a basic rule of thumb there are 12 Australian beef and sheepmeat plants accredited for chilled and 34 others accredited for frozen that are awaiting accreditation on chilled. I don’t know the exact number awaiting accreditation for China, with currently no listing as there have been a couple of audits last year – but it would be around 10. The number is always changing and only DAWR would have the correct figures at present.

New Zealand listings: There are 36 beef plants registered and 35 sheep meat plants registered in New Zealand. It should be noted that many NZ plants process both beef and sheepmeat, which are registered under the same establish number. For comparison sake, I have separated them out, as in Australia there are significantly fewer dual sheepmeat and beef plants.

It should be noted that in May 2017, China granted NZ the ability to trial for six months 10 meat processors to ship chilled meat to China. Prior to this Australia had the chilled market exclusively to itself.

US listings: The US in 2017 had 37 beef establishments approved – exports began in June, 2017 – allowing access for chilled, frozen, bone-in, and boneless beef products, plus a broad scope of offal products. The USDA has described the items that are eligible as follows: ‘China allows fresh and frozen deboned and bone-in beef products derived from cattle less than 30 months of age.’

In my opinion, Australia is likely to maintain a short-term advantage within China on grainfed chilled beef, should the tariffs on US beef be put in place – but chilled grassfed and frozen beef is likely to be highly competitive spaces. As stated earlier, the ability of US suppliers to capitalise on China is limited due to the availability of eligible no-HGP cattle with traceability since birth. New Zealand suppliers have also been restricted to accessing the chilled beef trade with only 10 eligible plants since May last year under a trial program, but with a limited grain industry in NZ, the focus has been more on grassfed chilled business.

As China’s demand grows the number of approved plants and countries will also increase and the number of eligible beef supply plants globally will become a crowded place. That is why it is vital that Australia establishes itself now in the Chinese market in the early stages of development, if it is remain a dominant player. The potential disruption to US chilled beef supply due to tariffs is likely to slow down the US momentum of the last seven months at a critical stage in China’s developing market.

Is the Hong Kong market the Achilles heel of US exports into Greater China?

The importance of Hong Kong to the US beef industry as a means of exporting to China cannot be understated. In 2017, the US exported 152,280t of beef to Hong Kong, representing 12pc of total US exports. If there was any disruption to Hong Kong exports, then US beef export pricing would see some downside. The announcement of the establishment of the State Market Regulation Administration (SMRA) could be the catalyst for this to occur.

The Chinese importer ‘questions and answers’ outlined above spoke of the amalgamation of the Chinese Mainland and Hong Kong inspection agencies, which some importers believe could potentially see the closure or dramatic slowdown of beef entering China through ‘grey channels’.

Other importers I spoke to believe the border is too porous for this to effectively occur, but it should be noted that it is in the interest of these importers for the grey-trade to exist and remain open.

In recent days the Chinese media has reported on the formation of the State Market Regulation Administration (SMRA) – the proposed restructure of government departments in China that would include some directly involved in market access for red meat.

The existing AQSIQ and CIQ is to be dismantled and absorbed into this new mega Chinese government department, called SMRA. Chinese media reports claim these proposed changes will occur over the next few months and is expected to give the new department more resources and enforcement tools and is in line with China’s objective of improving market regulation.

What is unclear is whether the new SMRA will also absorb the Hong Kong Food and Environmental Hygiene Department – and therefore tighten the grey trade as part of ‘improving market regulation’.

Time-line of events so far:

- March 2 – The US President announces a 25pc duty on steel imports and a 10pc duty on all aluminium product imports.

- March 8 – EU publishes a retaliatory list of items that they would introduce tariffs on as a counter measure to the steel and aluminium tariff

- March 10 – The US gives Australia, Canada and Mexico exemptions on the steel and aluminium tariffs.

- March 23 – The US steel and aluminium measures go into effect.

- March 24 – China signals it will retaliate against US tariffs – the Nikkei in Japan falls 4.5pc and Hang Seng 2.5pc on the news of the day

- March 28 – Chinese Premier Li Keqiang says he would rather expand trade and ‘pragmatically tackle friction and differences through dialogue and negotiation.’

- April 2 – The Chinese government included US pork on a list of 128 products that would be subject to a 25pc tariff, effective immediately

- April 3 – The US announces tariffs on 1300 separate items of Chinese imports – the value of goods would be $50 billion.

- April 5 – China’s Ministry of Commerce released a list of 106 additional US-made products subject to tariffs of 25pc in retaliation for the Trump administration’s proposed duties. The new list includes US beef and soybeans – the total value of goods matches the $50 billion worth of goods impacted by tariffs imposed by the US the day earlier. No start date for imposing these new Chinese tariffs has been announced.

- April 6 – President Trump asks US trade representatives to consider whether $100 billion of additional tariffs would be appropriate.

The response by the futures markets to the announcements by China and the US on tit-for-tat tariffs has resulted in a April Hogs futures market plunging 21pc in value since the announcement of tariffs on March 2. In the same period, April Live Cattle futures have fallen to a 7.5pc low. I do not claim to be an expert in US Pork, but to me, the fall in hogs does not make sense. I believe that common sense should eventually prevail.

The graphs above and the time line highlight how the US futures market on every piece of bad news has taken a serious step down over the last four weeks, since March 2 when the proposed tariffs on steel and aluminium was announced.

The downside reaction, I believe is disproportionate to what the fundamentals will show us.

There are three key points I believe to look at that shapes the value of hogs in relation to China:

- Firstly, the value of offals that go to China, which have few other market options, and rendering is the last resort at 10-15c/lb. It’s clear the market would pay the 25pc duty in preference to selling these items for next to nothing.

- Secondly, the cost of displacement of the pork meat that would have gone to China is a concern, but the value of this in a worst-case scenario is only 25pc lower price value (the cost of the additional duty). This, I think is an easy ‘worst case’ scenario to put a value on, and with China market 7pc of US pork exports, this means 25pc of 7pc. I estimate this is close to 2-3pc in US hog pricing, based on China’s tariffs – not huge numbers, and definitely not a 21pc fall in value that the market has experienced.

- Lastly, I raise the concern about too much protein with displaced US pork. The answers to this equation I believe lies in the USDA’s second quarter forecasts, with pork production expected to be up 4.8pc and beef up a whopping 12.8pc. None of this is new news, but at worst, if this was the underlying concern, surely the hogs value-fall would be more in line with the Live Cattle fall of 7.5pc – not 21pc.

It does not make sense to have hog futures at these levels. Whichever way you look at the negative impact on the value of offals, displaced pork or excess protein – none come within a bulls roar of a 21pc fall in value.

Eventually the market fundamentals I believe will reappear, and the hype and speculators fuelling the downside will be overridden by common sense. The market will realise that the style of negotiating the Trump administration is using with China is running out of steam and ineffectual, and that the cost of the tariffs to hogs is nowhere near the 21pc fall that has occurred.

In other words, a significant upward market correction is highly likely, I believe, in US hog futures pricing in the near future. US based analysts I have spoken to in recent days believe that the downward movement of hog futures has also dragged in part the US cattle futures lower – albeit at a much slower pace.

If I am correct and hogs rebound, then the impact on beef is potentially positive. It, too, is expected to rebound in a more moderate way. In other words the US protein complex is not as bad as some people think, and demand is in good shape. These fundamentals I believe have been lost in the market noise of the Trump administration’s announcements of the last four weeks.

* Simon Quilty is an independent Australian beef industry analyst. He can be contacted here.