ICBF technical director Dr Andrew Cromie and Australia’s Dr Rod Polkinghorne at the ICBF’s bull progeny testing centre at Tully in Ireland last week.

Ireland’s 100,000 beef and dairy cattle farmers are among the first in the world to face the challenge of dealing with legislated emissions reduction targets.

In July the Irish Government committed to a legislative framework that will require emissions from agriculture to be cut by 25 percent by 2030.

The legally binding pledge requires Ireland’s farming sector to cut emissions from current levels of 23 million tonnes to 17 million tonnes by 2030.

Some have expressed concern the targets will give producers no choice but to cull livestock numbers.

However, the technical director of the country’s innovative national testing program for cattle is confident the targets can be met through genetics and breeding improvements.

Ireland has a key advantage in this area that many other countries do not, due to a unique level of national cooperation on breeding decisions achieved two decades ago.

In 1998 more than 30 entities in the Irish beef and dairy cattle industries agreed to give up the genetic data they individually owned and controlled and share it in a collective central database for the benefit of the national industry.

That agreement led to the creation of the Irish Cattle Breeding Federation (the ICBF) as a single national body responsible for beef and dairy cattle breeding improvement.

The ICBF is a centralised, whole-of-industry-owned structure which provides national genetic indexes to guide genetic selection across Ireland’s national beef and dairy herds.

Its work has helped Ireland’s beef and dairy industries to achieve impressive rates of genetic gain and economic index growth in recent decades, which we have written about before.

The ICBF is already well advanced on a number of strategies which aim to reduce methane output from the Irish cattle herd.

These include the incorporation of methane traits into national genetic selection indexes, and encouraging earlier finishing ages of slaughter cattle.

Genomics strategy

The ICBF has been working for the past four years to gain an accurate understanding of methane emissions from Irish cattle by gathering emissions data on indoor finished cattle at its Tully bull progeny testing centre near Dublin.

That work is now being extended to include the measurement of methane data at grass to give a full lifetime assessment for the animal.

A portable Greenfeed unit

This involves the extensive use of portable US-designed Greenfeed machines for measuring cattle methane and carbon dioxide emissions in the paddock. The technology uses a feed concentrate to entice cattle to place their heads into the opening of each unit, where the gases they belch are measured and recorded against their individual RFID tags. (The same technology has also been used in Australia by Meat & Livestock Australia and the CSIRO).

Scientists at ICBF and Ireland’s livestock research and development body Teagasc have also successfully developed a novel new method to identify animals with genetics that produce lower methane emissions without losing productivity.

They have identified a trait they term “residual methane emissions” (RME) to define the difference between an animal’s actual and expected methane output, based on the quantity of feed that it consumes on a daily basis and its bodyweight.

Initial results have shown significant variation between cattle, with low RME animals producing 20 percent less methane, but maintaining the level of feed efficiency, growth and carcase output as the animals that rank high on the RME scale.

“The more efficient animals are making less methane,” ICBF technical director and geneticist Dr Andrew Cromie told a visiting group of Australian and US livestock scientists at the Tully research centre last week.

A Greenfeed machine in use in a paddock in Ireland. Picture: ICBF

“The goal going forward will be to have high beef merit animals in terms of the economic drivers but also with lower methane, and we’re very confident we can do that.”

Those results are based on a finishing diet at Tully, and work is now underway to confirm if they are repeatable in cattle finished on grass.

EBVs (Estimated Breeding Values) for grams per day of methane have been developed, and, in a world first, the ICBF expects to launch genomics for methane traits in Ireland’s national beef cattle genetic selection indices to help guide the selection of cattle with lower methane emissions.

Results from direct measurement of 1200 animals at Tully on growth, Dry Matter Intake and methane emissions per day showed Irish cattle were producing an average of 246 grams of methane per day, with clear evidence of differences across genders, systems and breeds, including within breed.

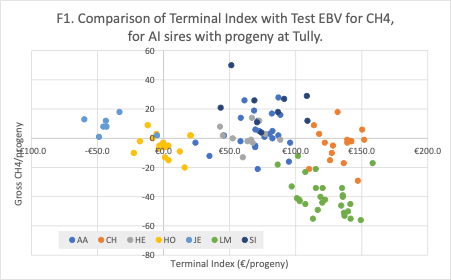

A chart depicting these results below shows that the higher terminal indexed animals have lower grams per day of methane, with the Limousin breed (denoted by the green dots) in particular demonstrating high efficiency with fast growth rates and lower feed intake.

Dr Cromie commented that while this might look very favourable for the Limousin breed at this stage, compared to other breeds on the chart such as Angus and Hereford, it is not the full picture. “We will only get that when we also include earlier finishing age. So the goal in the future will be hitting a target carcass weight and grade, at an earlier finishing age and with a lower grams per day of methane.”

Dr Cromie said the introduction of new traits into a national genetic selection index (such as grams per day of methane and earlier finishing age) would unavoidably cause some angst, as some bulls that have been popular and widely used in the past will not perform under the index.

“But we’re better to know that now and get the next generation of the ones we want into the breeding program,” he said.

“In many ways that is where an organisation such as ICBF has the big benefit, because you’re doing it for industry, it is not a point of difference for a breed or a breeder.”

The ICBFs research shows that replacement females in suckler herds bred through Artificial Insemination programs are also more profitable and more carbon efficient than stock bull bred females.

Current ratios using 2021 ICBF data indicate that 29 percent of 144,000 suckler replacement females were AI bred, 50pc were stock bull bred, and 21pc had no recorded sire.

The aim now is to encourage more herd owners to use high ranking Replacement Index AI sires when breeding suckler female replacements.

The ICBF believes the incorporation of methane traits into the national genetic selection indices has the potential to deliver in the order of 300,000 to 400,000 tonnes of mitigation in annual beef herd emissions.

Adding in terminal production of suckler bred and dairy beef cattle, plus also improvements on the dairy side (through improved female replacements), has the potential to take the total mitigation figure to about 1.2 million tonnes, Dr Cromie said, which is about 20 percent of the total government target.

Earlier finishing age

It is also thought that an even larger reduction – in the order of 1 million tonnes alone – can be achieved through management and system changes focused on achieving earlier finishing ages of slaughter cattle across Ireland.

Work from ICBF and other agencies to develop carbon footprint data incorporating lifetime emissions and feed and fertiliser requirements indicates that moving cattle in Ireland from being finished off grass in their third summer to their second summer can reduce lifetime carbon emissions by two tonnes per head.

Even achieving just a one month reduction in the finishing age could result in saving of up to 200 kg per head.

Government and industry initiatives are behind the push, with both now discussing options to pay cents per kilogram bonuses to producers to promote earlier finishing.

Dr Cromie said a key balancing consideration is to ensure the move maintains a science-based approach to optimising finishing age and does not result in higher cost systems for producers.

While Ireland is using a breeding approach to lower the methane emissions of its herd, the development of technology such as feed supplements that can reduce methane emissions could also benefit Irish producers in future.

Dr Cromie describes this as a potential win-win for the sector.

One challenge with the use of supplements is that it will create an ongoing cost which farmers and the industry would have to carry.

“So that is where breeding comes in, if we can crack the breeding one farmers can just get it, the better genes start to build up in the cow and cattle herd, generating animals that are lower in methane.”

Another interesting point was that analysis has shown that young bulls are producing lower emissions of at least around 50 grams per day compared to steers and heifers, through higher growth rates and more efficiency.

Whether this will result in future market pressure to replace steer production with young bull production remains to be seen.

Dr Cromie said Ireland’s cattle industry had come together and was taking the responsibility to meet the legislated emissions reduction target very seriously.

“We do not take the view that – ‘no we don’t believe that, you haven’t calculated that right’ – we have gone beyond that and said as an industry, that is the figure, we just better go and do it now, and that gets really good momentum there.”

HAVE YOUR SAY