Opinion

The recently announced staff redeployments at the CSIRO have generated a flood of media headlines about government cuts to science funding, and the apparent reversal by the Australian Government of recent policy aiming to encourage innovation and productivity growth in the Australian economy.

If you believe media headlines, (see here, here and here) the CSIRO is once again facing budget cut, resulting in hundreds of staff losses, and the Australian Government is once again demonstrating that although it talks the talk on innovation, it certainly doesn’t walk the walk when it comes to funding research and development.

However, before dashing off furious letters to the editor and joining protest marches, there are a couple of facts that need to be understood in relation to these announcements. Contrary to media reports, the recent announcement by CSIRO Chief Larry Marshall referred to redeployment of current CSIRO staff to focus on new priorities, and was not an announcement of ‘cuts’ to the CSIRO, which is reinforced by the statement that there is not projected to be any overall reduction in CSIRO staff numbers as a result of the changes.

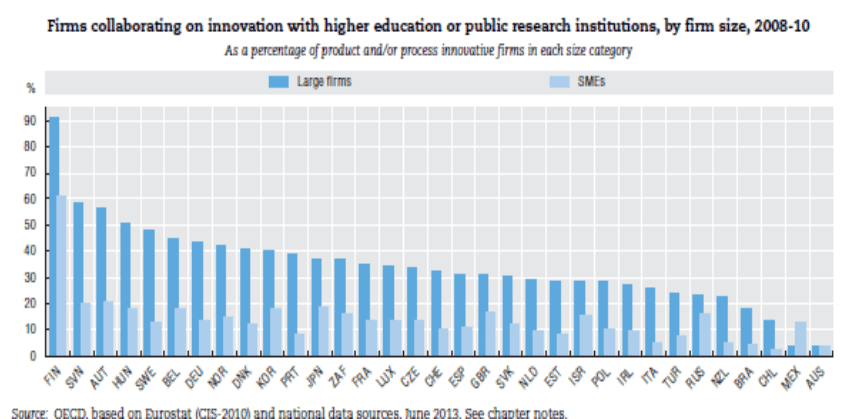

The second thing that needs to be understood is that Australia has an absolutely woeful record when it comes to collaboration between researchers and industry (the worst in the OECD as can be observed in the following graph – Australia is on the extreme right!) and that it is widely recognised that such collaboration is an absolutely critical requirement in fostering innovation, productivity growth and international competitiveness.

Clearly, there are major problems with current Australian policy settings relating to science and research and change is needed to fix the problem. The former Chief Scientist, Ian Chubb, made frequent reference to this issue in many of the speeches he made prior to his recent retirement.

Why does Australia have such a poor track record when it comes to collaboration between science and industry?

Why does Australia have such a poor track record when it comes to collaboration between science and industry?

Firstly, it is useful to remember that this was not always the case. In fact much of the success that Australia has had in areas like agriculture and mining were a result of very close and sustained collaboration between industry and researchers in the CSIRO and at universities.

It used to be broadly understood that Universities had the dual role of teaching, and conducting some of the more basic or ‘blue sky’ research that involved the development of new knowledge. The role of the CSIRO was to utilise that knowledge in the development of innovations that could be commercialised and taken up by industry (applied research), and hence innovation would be fostered in the economy. This is made pretty clear in the Science and Industry Research Act of 1949, which is the legislation that established the CSIRO. Clause 9 details the functions of the CSIRO.

Note that the primary function is to carry out research to assist Australian industry.

Over recent years the respective roles of Universities and the CSIRO have become less clear, for a number of reasons. One is the development of a “science for science sake” culture among staff of universities and some staff of the CSIRO, driven partly by promotion and funding structures that are fixated on publications (preferably international publications) rather than considering whether the research outcomes actually provide any national benefit beyond the accumulation of knowledge.

Under such reward structures, collaboration with industry can actually become an impediment to promotion and funding, especially if that collaboration does not lead to international publications. This culture is especially strong within the university system, where advancement up global university rankings in order to attract more international students and hence more revenue has become the key stated objective of most of the major universities. As a result, it is not surprising that the first task of any new postgraduate students is usually to start writing papers for scientific publications – even before any research is carried out. In addition, research involving theoretical desk-top modelling gets favoured, because it costs less and is a relatively easy way to produce a scientific paper.

The proposed redeployment of CSIRO staff from climate modelling to other areas with a focus on encouraging national innovation needs to be considered with the above issues in mind. It also needs to be considered against a backdrop of there being at least fifty major programs underway around the globe to develop and refine global climate models, many of these in nations with much larger science budgets that Australia. (For a list, see page 747). It is very difficult to imagine that Australia has any comparative advantage in this area of science, there are also significant programs underway at Australian universities involving similar research, and it is also very difficult to imagine there is much marginal utility in further refinement of existing Australian computer models, given global efforts in this area.

No doubt some will claim that the accuracy and reliability of Australian climate and weather forecasting will suffer as a result. However, it is already the case that many Australian farmers find that the Norwegian and Japanese weather bureau forecasts for Australia are more reliable that those produced by the Australian Bureau of Meteorology (BOM). The accuracy of the BOM forecasts will improve once its new computer is up and running, but the fact that the Japanese and Norwegians can accurately forecast Australian weather simply demonstrates the global nature of such science, and begs the question why Australia needs to have a major commitment in what is already a crowded global science area.

There is a lot that needs to be changed in Australian science in order to re-engage researchers with industry, and to create a greater focus on solving industry problems to bring about innovation, productivity growth, and ultimately improve the well-being of all Australians. Creating the right policy environment to make this happen to a greater degree will take time and effort, because many in the science system have become very comfortable with current arrangements, and consider that engagement with industry is a distraction from their ‘real’ role.

From the outside, the changes proposed for the CSIRO look to be an important step in the right direction, and have the potential to re-orient the organisation towards working more closely with industry to solve problems and to foster innovation and ultimately economic growth. It is also worth noting that the proposed changes seem to actually reflect the role that was envisaged in the CSIRO’s founding legislation.

Mick Keogh is the executive director of the Australian Farm Institute. This article originally appeared on the AFI website and is republished here with permission from the author. To view original article click here

Once again Mick Keogh nails it!