THE Queensland beef industry may be suffering a $100 million annual impact from the effects of hydatids, an estimate carried out by beef processor Teys Australia suspects.

That staggering figure, based on data flowing out of the company’s expanding abattoir animal health reporting systems, is based solely on lost beef yield per carcase, or weightgain – not on the losses associated with livers and lungs condemned due to hydatid infection during the inspection process.

The company’s findings are supported by recent research conducted by Charles Sturt University student Cara Wilson, carried out as part of her now-completed PhD studies.

Teys Australia’s John Langbridge

“We see the effects of hydatids in carcases on a daily basis,” Teys Australia’s Dr John Langbridge told Beef Central.

“In one well-known scientific trial conducted earlier, over a period of 12 months there was a difference in growth rate of 12-13pc between animals exposed to hydatid infection, and those without,” Dr Langbridge said.

“That’s loss at the farmgate, as well as to the processor. From an animal disease point of view, that is really significant.”

The economic impact from hydatids was a difficult problem to resolve, Dr Langbridge said, because the parasite’s life cycle involved the intermediate host (a wild dog, wild cat, fox or pig), and the final host, in beef cattle or sheep.

A vaccine for hydatids has been developed for sheep and was in commercial use in some overseas countries, and preliminary development work is taking place for cattle (see more below).

“Getting a better understanding of the cost of the disease will allow drug and vaccine manufacturers to put the argument to producers over justifying the expense for treatment,” Dr Langbridge said. “It could well be that at some future time, feedlots may pay a small premium for cattle vaccinated against hydatids.”

He said the roll-out of more detailed animal health reporting on slaughter cattle was helping the industry better understand the productivity cost impact from such diseases.

“This has to be done over a sequence of seasons, and across multiple locations, which will give us a better picture of what diseases like hydatids do, and the cost impact,” Dr Langbridge said. “Then the industry and commercial animal health companies can then look at what’s worth investing money into, to try to find a fix.”

Dr Langbridge said the financial impact of hydatids up to now had clearly been under-estimated.

“Most people know that hydatids have had some negative effect, but they didn’t know how much. The perception of the predation damage being done by wild dogs is probably only the tip of the iceberg, when the true cost of hydatids (spread by wild dogs) is taken into account.”

He said in addition to hydatids, there were other parasites that could be carried by wild carnivores that were only now beginning to be recognised. An emerging example was sarcosporidia, which caused an allergic reaction to the parasite’s larvae as they migrate through the animal.

In Teys’s case, about 600 carcases each year are condemned due to the sarcosporidia parasite’s impact – and the incidence had in fact grown from about 200 carcases each year a decade or so ago.

Such data on hydatids damage was also instructive to people involved in feral animal control, he said.

PhD study finds wider impact

Charles Sturt University PhD graduate Dr Cara Wilson’s research through the Graham Centre examined the ‘direct’ impact of hydatid disease on the beef industry in eastern Australia. Her work focused on ‘direct’ impacts being seen through liver and lung condemns, rather than the harder-to-measure ‘indirect’ weightgain impact.

Dr Cara Wilson inspects beef livers during her PhD project

As part of her research, Dr Wilson examined data from 1.1 million cattle slaughtered at a focus abattoir between 2010 and 2018.

She found the geographic distribution of hydatid-infected cattle was wider than previously thought, with losses to the abattoir of more than $650,000 in downgraded carcases.

“Hydatid disease in beef cattle has important epidemiological and economic impacts on the Australian beef industry,” she said.

One of her conclusions was that improved knowledge and awareness of hydatid disease among Australian beef producers was required, and practical and cost-effective control measures needed to be identified.

The overall objective of her thesis was to determine the importance of hydatid disease to the Australian beef industry and to gain a deeper epidemiological understanding of this disease.

Part of her study also looked at the knowledge, attitudes and practices of Australian beef producers over management and understanding of the disease.

Routine post-mortem meat inspection at the focus abattoir produced an apparent prevalence of hydatid disease using the abattoir data of 8.8pc.

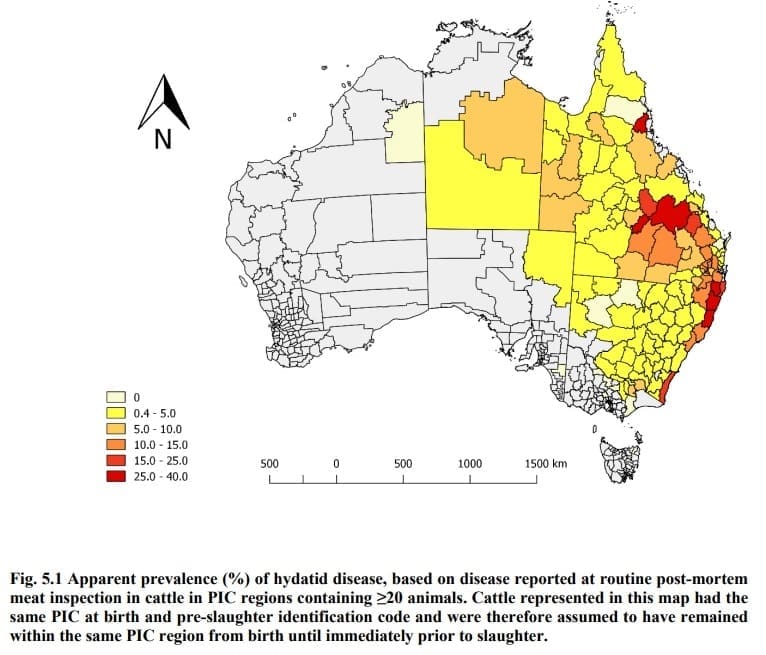

“The identification of infected cattle in almost all sampled regions demonstrated that the geographic distribution of hydatid-infected cattle is also wider than previously thought,” Dr Wilson’s thesis said.

The odds of hydatid disease were found to be highest in eight-tooth cattle, and cattle that were grass finished.

The median estimated direct annual loss to the focus abattoir between 2011 and 2017 was $655,560, equating to about $6.70 lost per infected animal. Direct losses varied each year of the study and ranged up to $163,000 in 2014.

Dr Wilson stressed, however, that the assessment was most likely an underestimate – therefore, these losses indicate that hydatid disease has a substantial economic impact on the Australian beef industry.

Hydatids endemic across Australia

Hydatid disease in Australian cattle is endemic, and has been reported in all states and territories, however there are defined regions where the parasite appears to have a higher prevalence. These are generally coastal areas, or elevated areas associated with the Great Dividing Range.

One study reported a prevalence of 28pc in cattle east of the Great Dividing Range, and just 3pc to the west in northern Queensland. In contrast, less than 1pc of both sheep and cattle have been reported infected with the parasite in Western Australia.

Few studies have been conducted to estimate the productivity losses resulting from infection with hydatid cysts, Dr Wilson’s thesis said – nor was there any standard method for evaluating losses associated with hydatid disease in livestock.

Some studies evaluated organ losses based on liver condemnations alone, while others evaluated losses from all affected organs. Those studies that also included productivity losses varied in the productivity losses (weightgain, fecundity, hide value) included in their analyses.

Economic losses associated with direct losses such as condemnation and downgrading of infected offals have previously been shown to be only a small proportion (perhaps between 1pc and 24pc) of the possible total economic losses resulting from this disease in livestock, the thesis said.

Although reduced productivity in hydatid-infected livestock has been reported, and production losses have been reported for other parasitic diseases such as liver fluke, the evidence was considered too uncertain to be included in this study.

“Studies need to be conducted in each region to determine the economic impact of hydatid disease on the specified livestock industry,” Dr Wilson said.

“Productivity losses have not been widely considered when estimating economic losses due to hydatid disease in Australian cattle,” she said.

“Importantly, in Australia, cattle are sent for slaughter when they meet certain market specifications such as weight. Therefore, even if the weightgain of cattle is reduced by hydatid disease, producers will tend to keep those cattle until they reach the desired weight,” she said.

Weight differences at slaughter could also be confounded by a variable that was not available during the slaughter statistical study, such as breed.

Awareness

Hydatid disease was a ‘silent disease’, and as such, many producers might not perceive it as a risk without evidence of disease and systematic reporting, Dr Wilson’s thesis said.

“Hydatids in beef cattle has important epidemiological and economic impacts on the Australian beef industry. Improved knowledge and awareness of hydatid disease among beef producers is required, and practical and cost-effective control measures need to be identified,” she said.

The results of surveys conducted as part of her PhD demonstrated that producers do not feel informed about hydatid disease, but would take action against it if they knew their cattle were infected.

Increasing knowledge and awareness of hydatid disease among beef producers is likely to encourage adoption of currently available disease control strategies, Dr Wilson said.

Education to improve knowledge could be in the form of extension materials such as factsheets or workshops which provide information on disease preparedness and control.

Vaccine prospect

A vaccine that prevents hydatid disease infection in cattle could reduce the number of organs condemned or downgraded due to hydatid disease, reduce weightgain loss and potentially lead to a considerable economic saving for the Australian beef industry, Dr Wilson said.

The EG95 vaccine, an experimental vaccine originally developed for sheep in the late 1990s, had been modified for administration to cattle and is currently registered for use in China and Argentina.

Vaccination did not eliminate established cysts, but can prevent subsequent infection from occurring in cattle. When used in cattle at five times the dose for sheep, and administered twice with one month between dosages, the vaccine achieved 90pc protection in cattle experiments compared to unvaccinated cattle.

Protection was shown to last for 12 months, but a third vaccination 12 months after the first two increased the protection to 99pc compared to unvaccinated cattle and maintained protection for a further 11 months.

Further surveys are needed to investigate producer attitudes towards use of vaccines, to determine whether the EG95 vaccine would be practical and convenient for producers to implement on-farm.

Why is there no mention of hydatid disease in humans?

We felt the story was already lengthy, John – but recognise the significance of hydatid disease in humans, as well as cattle. We’ll try to cover that in a separate workplace health & safety story. Editor

This is very interesting. I had not noticed the lower weights in hydatids-affected carcases. Will watch out for it.

Thanks for your comment Mark. Since we published the article, Teys has provided some figures on how they arrived at their estimate of $100m impact from lost weightgain in QLD.

QLD accounts for about 5m slaughter cattle annually. About 60pc of those have hydatids, or 3m cattle. Multiply that by $33/head in compromised weightgain, makes the estimated figure of $100m somewhat conservative. Editor