THE red meat industry can learn a lot from the dairy sector’s chequered history in the China export market, livestock industry stakeholders attending a conference in Melbourne last week heard.

Rabobank economist Tim Hunt

Speaking at the Platinum Primary Producers annual conference, agricultural economist Tim Hunt focussed on the China opportunity for animal protein, and some of the fundamentals that would shape that, using dairy’s earlier lessons as an example.

Mr Hunt is the general manager of food and agribusiness research and advisory with Rabobank.

He suggested there were three key features of the Chinese food industry that shaped almost everything that goes on there, to some extent:

- China is rich in resources and has enormous amounts of arable land and water, but relative to its vast 1.4 billion population, is relatively poor in those resources. In terms of arable land per person, for example, it has 0.1ha per person – less than half that of New Zealand, and less than a quarter of the ratio in Brazil and the US. China knows very well that as it gets richer, and more populous, it cannot possibly hope to produce all the food that it would like, Mr Hunt said.

- Older Chinese people can still recall food export embargoes for political reasons and famine, in the late 1940s-early 60s. Between 13 and 20 million people died of starvation in the 1960s, heightening sensitivity to food security. “They remember what it is like to run out of food, and don’t want to be at the ‘strategic mercy’ solely of offshore food suppliers,” Mr Hunt said.

- Chinese citizens have clear and often well-founded concerns over food safety and quality of domestically-produced foods. Adulteration of milk powder with melomine was a well-known example. The extent of that practise across the supply chain was alarming to many Chinese people.

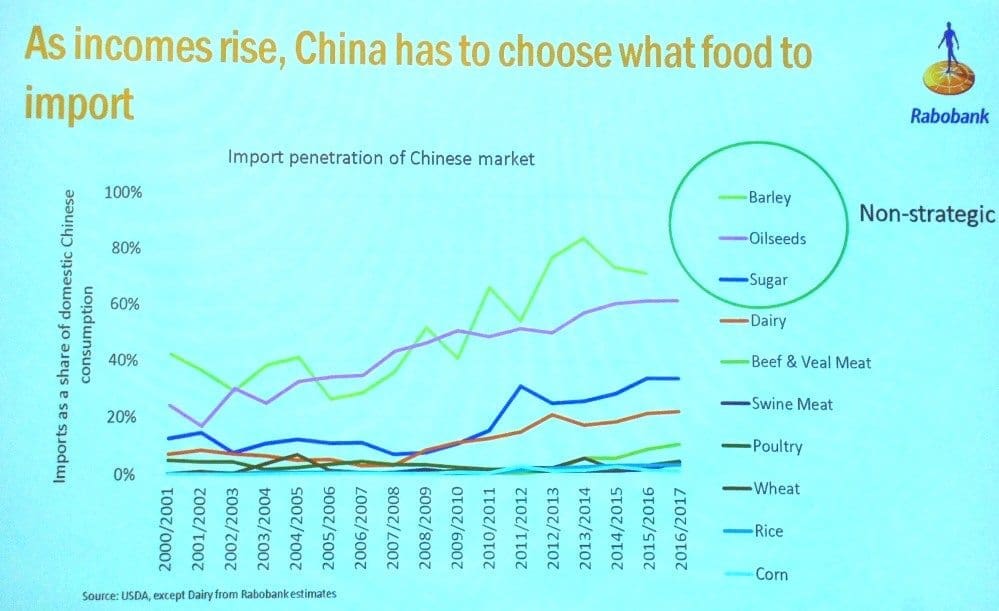

Mr Hunt said as Chinese incomes rose, an interesting point was which food groups the country would choose to try to produce itself, and which it would choose to import. He used statistics covering import penetration in a range of food products since 2000 – they year that China joined the WTO – to illustrate his point.

In certain non-strategic products, like barley, oilseeds and sugar, China has recognised that it cannot keep up with domestic requirements, and is happy to import a lot more of its needs, going forward – ranging from 40-80pc of total demand for those commodities.

At the other end of the spectrum, products like wheat and rice only made up a very small percentage of import penetration (see graph). “These are staple parts of the Chinese diet where the government has clear policy around being as self-sufficient as possible. This is underpinned by domestic subsidy or price support schemes,” Mr Hunt said.

Where it gets interesting is the space between the two extremes, filled by dairy, beef, poultry and pork.

“China is yet to really decide whether these are strategic commodities, or not, and that will really impact on the ability of a product like imported beef to penetrate the Chinese market,” Mr Hunt said.

“In dairy, China has at this stage emphasised that it would rather have a safe supply chain, than necessarily be self-sufficient. It’s not a core part of their diet, and has been comfortable to introduce policies that mean greater reliance on suppliers offshore who can produce more efficiently, and who are arguably safer, to supply a lot of their market requirement.”

In beef and veal, import penetration was starting to rise, but still only accounted for about 10pc of all consumer requirements. Add grey channel beef smuggled in from Hong Kong and Vietnam, and that figure was probably closer to 15pc.

“Beef is starting to make inroads, and it is my view that beef is now being regarded as a ‘non-strategic’ food item by the Chinese authorities,” Mr Hunt said. “That suggests they will be comfortable seeing more growth in imported product, going forward.”

Growth story is often ‘over-sold’

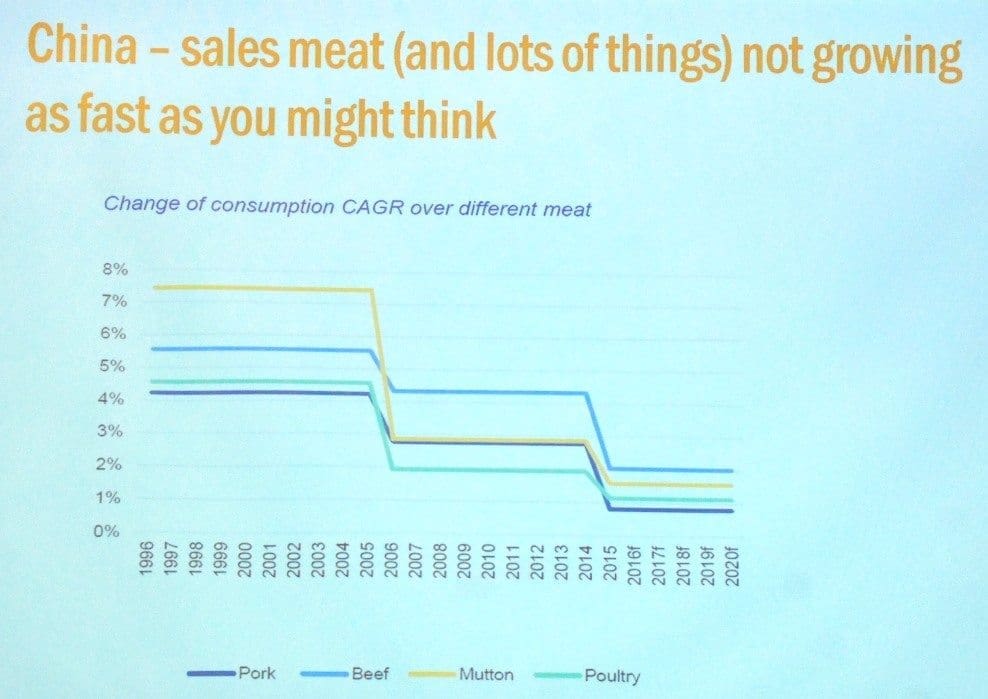

Mr Hunt said there was a tendency for over-selling of the story of how quickly China was growing, and how quickly consumption of products was expanding.

“It’s a vast market, so even if it grows slowly, it is still a considerable opportunity. But the opportunity in food, as was the case earlier in dairy, is as much about the supply side of things as the demand side.”

He presented this slide showing earlier annual beef demand growth (from all domestic and imported sources) of around 6pc, falling to around 2pc since 2015, and following a similar pattern as pork, mutton and poultry.

“The economy in China is still growing, but not nearly as quickly as it was, and population growth is now only about 0.5pc per year,” Mr Hunt said.

Consumption rates of such products were starting to reach reasonably high levels in larger population centres on China’s eastern seaboard, and a number of them were becoming increasingly expensive.

“This is pretty much the exact same story we saw in dairy, five years earlier: rapid growth at the start, slowing down quite considerably, with people still looking at imports,” he said.

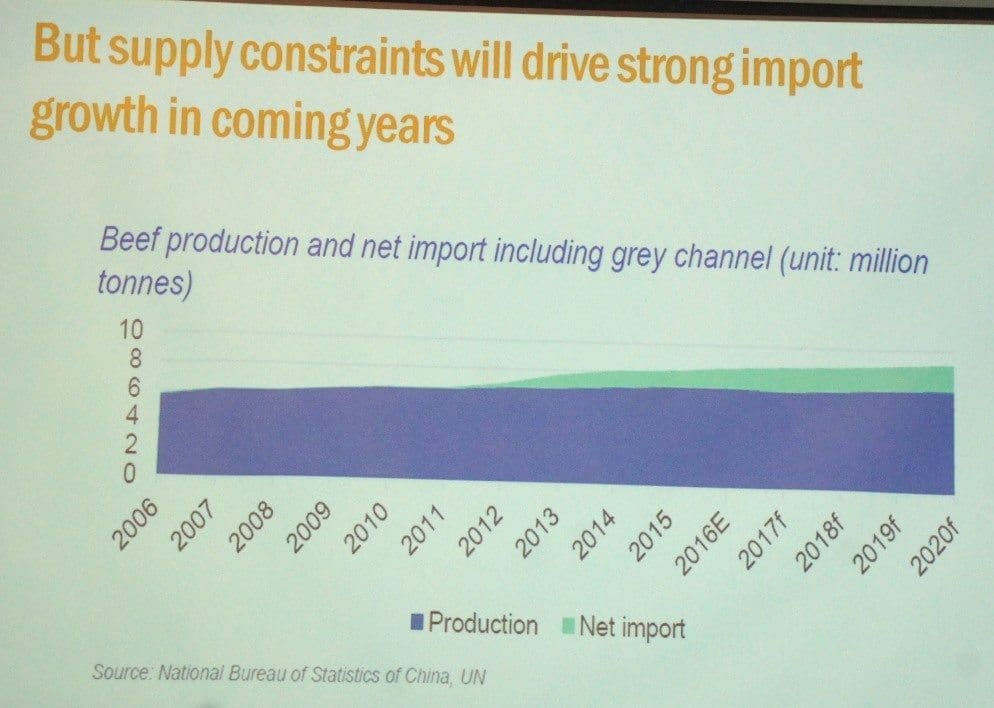

“It’s argued that half the excitement around animal protein will come from the fact it is big, and growing, and around the supply constraints and what they will prioritise.”

Rabobank ’s expectations are for future annual growth in beef sales in China of around 2pc per year, much of it accounted for by imports.

“Our best estimate is that imports (direct and grey channel) will rise from around 15pc of China’s total beef consumption today, to around 20pc by 2020, generating some really good growth,” he said.

“But that view is as much about supply constraints, as it is about demand.”

On sheepmeat, more potential was seen to expand production and improve genetics in the domestic Chinese flock, meaning current imported market share of 5-6pc was only likely to rise to about 7pc by 2020.

In terms of where sales for additional red meat will occur, recent rapid growth in eating out will continue in China, Mr Hunt said, as will the e-commerce segment. Traditional retail sales (all commodities) are forecast to grow at 6pc per annum, while e-commerce is expected to grow at 20pc.

Learning from dairy experiences

Mr Hunt said the way the red meat protein market was evolving in China reminded him a lot about what happened earlier in dairy imports.

“We’d be crazy not to look at some of the experiences that the export dairy industry has had in the last decade, as beef and sheepmeat continues to penetrate the market,” he said.

The first lesson was that ‘first-mover’ advantage had proven considerable in gaining position in the Chinese market.

“Even before dairy imports took off around 2008-09, New Zealand had been working hard on the Chinese dairy industry, especially with whole milk powder.

“New Zealand got in early (it established its FTA with China in 2008), and that’s why China today is still principally a whole-milk powder market, rather than a skim-milk (protein only) market.”

Because NZ got in early, they had a reasonably long period before the market took off, allowing them to advocate that NZ product was by far the best in the world.

“On my first trip to China eight years ago, I was struck by how all the procurement managers we met thought NZ dairy product was a step above anything else in the world market. When asked why that was, it was clear there was a little bit of substance to that, but there was also a marketing angle.”

“And one of my Chinese colleagues explained at the time, the Chinese love to have a hierarchy of things: certain counties are deemed as the ‘best’ at producing different items – they want ‘cars’ from Germany, ‘wine’ from France, and believe it or not, ‘disposable nappies’ from Japan. And they want milk powder from NZ, and that ‘halo’ effect is still evident, to some extent, today.”

A good example of how ‘first mover’ advantage had worked for NZ in dairy came in 2009, when Coca Cola launched a dairy product into the Chinese market, strongly linking to NZ as the source, which had real cache among consumers.

New Zealand is now shipping around four billion litres of milk annually into the Chinese market, or around 25pc of all exports.

“But there is general recognition that if you are going to rely that much on one market, and you are going to get that much access to sell the product, you better do something for them. I believe that was part of the reason why NZ has invested in production units within the Chinese market – to get a comfortable balance between capitalising on the market, versus investing on the ground, to help the Chinese dairy industry.”

“It’s a strategy we’ve seen replicated by others, balancing access with investment on the ground.”

But despite all the access NZ dairy got and the investment on the ground in China, the harsh reality was that as an offshore supplier, NZ was always going to bear the brunt of any market adjustment.

“This was a very harsh lesson for NZ dairy, particularly in 2015,” Mr Hunt said.

Chinese imports in whole milk powder, at their peak, were more or less doubling every quarter. But when they suddenly realised that the market had slowed down a lot more than they thought it would, and had excess product, they slashed NZ imports by 50pc.”

“One year China was expanding imports every quarter by 150,000 tonnes; the next year they were pushing it down by 150,000t. It created enormous volatility in the largest market for NZ product in the world. For the five years prior to the push-back, Chinese milk prices sat at a 40pc premium to NZ milk prices. What happened when the market went into excess was that milk prices in China only reduced a little, and they continued to pick up their own domestic milk, while NZ milk powder prices fell to one third of the Chinese price.

“It made zero economic sense for China to keep buying their own milk, rather than import the cheaper NZ product, but the harsh reality of this scenario – and I would bet we are going to see it again in other industries – is that they want your supply to grow the market, but when it hits the fan and they have too much product, it’s going to be you that bears the brunt of any adjustment.”

A lot of the supply chain strategy that’s been seen in corporate investment has been in trying to avoid such circumstances, Mr Hunt said.

Rising trade flows out of the NZ and Australian dairy industries had inevitably seen Chinese investment in the industries in both countries.

“The aims of this are several-fold. Partly its around return on investment – they can see the growth into their industry, but there’s also some value seen in trying to set up a wholly-controlled supply chain, and then market that to the end consumer.

“It’s an interesting lesson in how things evolve. Firstly in China it was just about selling milk; then it was about milk from NZ, because that was seen as premium; and now it is imported NZ milk from a supply chain that we have control over. As the businesses look to extract premiums, those things are all important.”

HAVE YOUR SAY