Measuring flight speed in Brahman weaners exiting the crush, tripping two light beams (tripods).

IN discussing selection criteria with producers, the most commonly cited priority is temperament.

This response is reinforced through industry research, such as the Angus Australia Beef Breeding Insights, which identified temperament is the highest ranking criteria for breeders, over and above visual appraisal, bull health checks or EBV information.

This focus underlines the impact poor temperament can have on any beef enterprise. Crossing over workplace health and safety for livestock handlers, to animal welfare and economic issues associated with carcase damage and poor eating quality, temperament is a trait that should never be neglected.

As a genetic trait, temperament is moderately heritable, and so the opportunity for producers to work towards improving their herds can benefit from genetic information. Within a number of breeds, EBVs that address both docility scores and flight speeds offer producers the opportunity to rank potential sires according to individual needs.

However, while genetic selection does offer producers the opportunity to search and select for bulls that may offer an improvement in their herd, it is essential to remember that genetics alone won’t fix an issue.

Temperament is perhaps best described as an animal’s ability to consistently behave in the same way, as a response to stress or environmental challenge. Knowing the genetic background of an animal’s response, either in docility testing or flight speed, offers some key insights into animals’ consistent response in events that place cattle under some stress.

Temperament is perhaps best described as an animal’s ability to consistently behave in the same way, as a response to stress or environmental challenge. Knowing the genetic background of an animal’s response, either in docility testing or flight speed, offers some key insights into animals’ consistent response in events that place cattle under some stress.

While this is a useful starting point, it is important to recognise that stress or environmental challenges can be created through other means.

Movement of stock from paddock to paddock, regrouping and drafting new mobs, or extensive mustering all fall within the category of additional stress.

Both research and experience highlight that young animals often have greater variation in temperament – their ability to cope – than that displayed by older cattle.

It is also well proven that cattle can become habituated to methods of interaction with each other, handlers and other forms of stress they may experience on farm.

The key message underlining selection for improvement for temperament is to ensure there is an equally strong focus on management and handling practices that are undertaken on-farm.

These key areas, commencing with weaning will imprint on an animal’s response to handlers, infrastructure and movement practices. Ultimately poor handling and movement practices can override any decisions made in selecting for better temperament.

Proactive selection would focus on setting criteria around an animal’s behaviour at critical points in its life, such as marking and weaning, as well as ongoing observation across the animal’s lifetime. While not always used in commercial situations, recording crush or flight speed can be a repeatable and objective method of identifying animals that have a less desirable temperament.

In addition to identifying and removing animals from herds that have poorer temperaments, there are opportunities to use formal assessment techniques such as flight time recording to identify and select animals more suited to particular finishing environments.

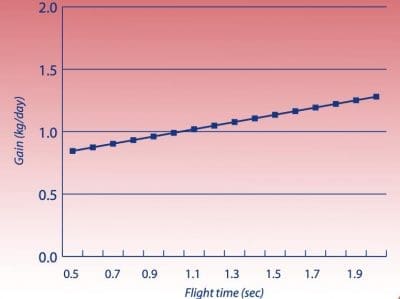

Work by the CRC highlighted the differences in feedlot performance between animals with low flight times (better temperaments) and faster animals.

Relationship with feedlot daily gain

Relationship with feedlot daily gain (Source Beef CRC)

One experiment with British breed cattle resulted in no animals with slow flight scores being pulled from pens for sickness reasons. This contrasted with the results of animals with faster flights speeds, where some 42pc of those animals being taken to the hospital pen at some point during feeding.

These results are in addition to other work highlighting the difference in daily weightgain between groups, which identified those cattle with slower flight times growing faster, to heavier weights and having better feed conversion ratios.

While flight times can be reduced as animals become more habituated to the process, the consistency of behavior results in no real change among groups of cattle. Mainly the faster animals, will still be the fastest (most flighty) and the slower animals will remain the slower animals.

This can offer producers the on-farm advantage of selection and marketing cattle towards more suitable end markets, as well as selecting replacement heifers from the groups that offer the best temperament within the environmental conditions of the business.

Longer term, these on farm practices, combined with use of high accuracy EBVs for docility and flight speed, can significantly achieve improvements across a herd.

Alastair Rayner is the Principal of RaynerAg, an agricultural advisory service based in NSW. RaynerAg is affiliated with BJA Stock & Station Agents. He regularly lists and sell cattle for clients as well attending bull sales to support client purchases. Alastair provides pre-sale selections and classifications for seedstock producers in NSW, Qld and Victoria. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au

Alastair Rayner is the Principal of RaynerAg, an agricultural advisory service based in NSW. RaynerAg is affiliated with BJA Stock & Station Agents. He regularly lists and sell cattle for clients as well attending bull sales to support client purchases. Alastair provides pre-sale selections and classifications for seedstock producers in NSW, Qld and Victoria. He can be contacted here or through his website www.raynerag.com.au

I would suggest that flight speed is only one measure of temperament

And my experience is that animals increase their flight speed with repeated passes and the short distance ( 1.8 m or one panel ) it is generally measured over introduces a significant error wrt where the animal “breaks” the light beam , nose or chest etc . A longer distance would reduce this error factor

Whilst flight speed corelates well with performance and eating quality , I would suggest it is only one measure of temperament and other measures may be more appropriate for selecting females for replacement

The old test of putting you over the rails is still the tried and proven one but others should be considered

I have used different methods

How far they run out in the yard after exiting the crush is a good indication . The ones that run to the far rails should be culled

The crush score is problematic as some can be seen to be still but on closer examination are quietly trembling . I would not call this docile?

Does this just measure a fear of being confined?

I have found another good measure is simply confining them in a smallish pound . Many who pass the other tests will become agitated . I would call this separation anxiety and one mate suggests it seems to be most pronounced in African breeds .

By concentrating only on flight speed we are only measuring one aspect of temperament . I suggest that other measures should be included to give a better overall measurement especially for selecting females