The “Golden Triangle” is the infamous 1970’s heroin smuggling region surrounding the point where the borders of Myanmar, Thailand and Laos meet.

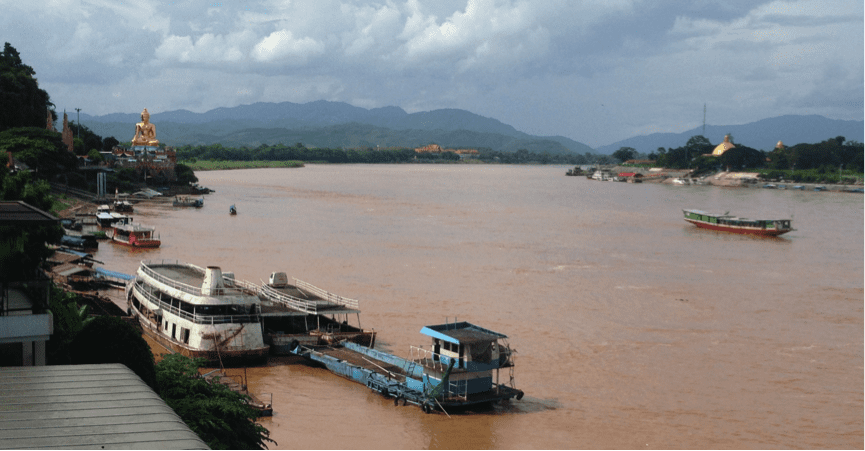

In the photo of the Mekong River above, the golden Buddha on the left is in Thailand, the red roof in the middle is in Myanmar and the golden dome on the right is in Laos. This is the physical centre of the golden triangle.

The long red and green vessel on the right is a Laotian cattle boat which has just loaded up with about 60 head of cattle or buffalo in Chiang Saen (Thailand) bound for the port of Mongla in Myanmar about two days sailing upstream.

Today the Golden Triangle river-port town of Chiang Saen is the busy centre of a legitimate trade route linking Thailand, Myanmar and Laos with China’s southwestern province of Yunnan via the mighty Mekong River.

It’s also a major tourist destination with attractions from museums explaining the history of the opium trade to casinos and golf courses.

This is not the highest quality map but it helps to demonstrate the location of the Golden Triangle, which is centred around the Thai river town of Chiang Saen. The town is just north of Chiang Rai which can be seen on Thailand’s northern border on this map.

This story is yet another powerful example of the game-changing demand and supply reversal which has recently taken place in China.

Once the previously massive Chinese domestic cattle herd was no longer able to keep up the required supplies, booming Chinese demand forced traders to source product from outside the country.

And logically, the first place to start is just across the border in Myanmar, Thailand, Laos and Vietnam.

The family of Chiang Saen businessman, Eddy Wongwan, have been trading agricultural products on this river for generations.

One of their many family businesses was the importation of slaughter buffalo down the Mekong from China into Thailand.

In 2007 the supply of buffalo from China suddenly dried up.

After a break of about three years, the trade started up again, but in the reverse direction.

Eddie now allows the Thai Quarantine Department and livestock exporters to use his riverbank port in Chiang Saen to assemble and dispatch about 300 buffalo and 300 cattle per day, five days a week.

After a voyage of about two days upstream the animals are discharged into a Myanmar holding facility at Mongla where they are rested for a few days before being trucked across the Chinese border only a few kilometers away.

The ownership of these animals changes hands on the Thai farm where the Chinese agents buy the cattle and buffalo (males only) on a live weight farm-gate basis.

The following day the stock are trucked to the Chiang Saen port facility where they are loaded onto the river boats after being provided with the necessary documentation by the Thai officials.

Payment is completed once the stock have been delivered to the port ready for loading.

The prices paid for these export cattle (AUD$4.80 per kg live) represents a premium of about 30pc over domestic slaughter rates.

The “Grey Route” is a fascinating concept in which the Chinese government allows the importation of products that are actually illegal. This approach is really only a problem for us Westerners who have been taught that government regulations are black and white. In many countries around the world, regulations are black and white and grey.

By adopting this approach, the grey route allows the Chinese government to respond to sudden commodity shortages in order to ensure adequate supplies of product are imported even though there has not been time to conduct the necessary trade negotiations and develop suitable regulations and associated protocols.

Government officials can publicly claim that they definitely don’t allow the importation of Indian beef because it does not comply with the relevant trade rules and health protocols.

At the same time, simply by turning a blind eye, the government can ensure that sufficient box beef and livestock is imported to satisfy raging demand and help to keep a lid on food inflation.

A sensible and pragmatic approach really, when the fact is that the bio-security risks for China are minimal.

In the meantime, new policies can be developed to address the shortages while trade negotiations can proceed at their normal glacial pace and eventually, official trade policy and regulations will catch up and match with commercial reality.

The recently completed Chiang Saen port a few kilometers down-stream which will soon be the new location for loading livestock.

- To read more articles from Dr Ross Ainsworth click here to visit the South East Asia Report page in Beef Central’s live export section, and to visit Dr Ainsworth’s regular blog click here

HAVE YOUR SAY